August 31st, 2013  Edward Bernays (1891-1995) It may have been a patient (I can’t recall) who suggested I search online for the 2002 BBC documentary by Adam Curtis called Century of the Self. It turns out the video is freely available at several sites; the full four-hour documentary can be viewed or downloaded here, or each of the hour-long installments here. In briefest outline, Century of the Self advances the thesis that Freud’s views of the unconscious set the stage for corporations, and later politicians, to market to our unconscious fears and desires. It’s gripping, it explains a lot, and it reminds me of The Matrix in the way it portrays an ugly dystopian truth hidden behind bland normality. Except Century of the Self is real, not science fiction.

One reviewer offers: “There are very few movies I wish I could force my friends to watch, that I feel encapsulate a feeling that I’ve had but have been unable to articulate.” Indeed, Century of the Self ties together several observations I myself have made over the years about corporate marketing — and then it goes much further, placing those observations in a broad context. For example, in my youth I found it odd that any products at all could be marketed to hippies, those bastions of non-materialism. Yet by the early 1970s the signature unkempt long hair became a “style” featured in fashion magazines and offered in hair salons, and blowdryers were widely sold to cater to this new look. Less than a decade later, punk rockers pierced their clothes with rows of safety pins, and it wasn’t long before Macy’s sold brand new clothes with safety pins already inserted. Goth, grunge, hip-hop, or hipster, it doesn’t matter. Products will be sold. As the Borg say: “You will be assimilated. Resistance is futile.”

I noticed something similar at the other end of the materialism continuum as well. By the 1980s, expensive, formerly niche products were being avidly marketed to ordinary consumers. Regular cooks bought restaurant-grade pots and pans, average shutterbugs purchased advanced cameras, families who never left the suburbs drove SUVs that could go off-road and up mountainsides. What motivated people to spend their hard-earned money on features they’d never use and quality they’d never fully appreciate? Again, it was hard to escape the conclusion that corporations sold self-image and emotional aspirations, not rational goods and services.

I’m old enough to remember when “lifestyle” was first popularized as a sales term, and when pitches aimed at self-image were still a little ham-handed and obvious (e.g., “What sort of man reads Playboy?”). Now we fail to notice that it is literally impossible to sell a new car, or prescription medications to the public, with an appeal to rationality. No one even tries. Back in the mid-1970s it was novel and slightly jarring when gasoline companies ran ads not (directly) to sell gas, but to improve their corporate image. We’ve come to accept that as routine nearly 40 years later.

It hasn’t always been so. Century of the Self shows how advertising once aimed to influence rational choice. This gave way in the early 20th century to advertising aimed to connect feelings with a product. Amazingly enough, at the root of this change was Sigmund Freud’s nephew, Edward Bernays. Bernays, an American propagandist in WWI, applied his wartime experience and his uncle’s theories of the unconscious to peacetime commerce. He invented the field of public relations, popularized press releases and product tie-ins, and changed public opinion about matters ranging from women smoking to the use of paper cups — all to increase sales. Viewing politics as just another product to sell, Bernays also helped Calvin Coolidge stage one of the first overt media acts for a president, and helped engineer the 1954 coup in Guatemala on behalf of his client the United Fruit Company, by painting their democratically elected leader as communist.

This and more happens in just the first hour of the documentary, titled “Happiness Machines.” The second hour, the weakest in my view, is called “The Engineering of Consent” and focuses on the ascendancy of psychoanalysis and Anna Freud’s consolidation of power. The point here is that the unconscious was seen as a dangerous menace that needed to be kept under lock and key. Rational choice, especially by crowds, was unreliable under its influence, so “guidance from above” (in Bernays’ words) was needed from political leaders and corporations for the public good. The conformity and mass-marketing of the 1950s reflects this view of a public that cannot be trusted to think for itself. The pendulum swings the other way in the third and best installment, “There is a Policeman Inside All Our Heads [and] He Must be Destroyed.” By the 1960s the human potential movement urged the expression of impulses instead of their repression. Business was eager to help. By marketing products as a means of self-expression, business turned from channeling public impulses to pandering to them. There is a fascinating discussion in the film about political activism being co-opted in this process: making the world a better place gave way to making oneself better in ways that, not coincidentally, required buying more goods and services. The final segment, called “Eight People Sipping Wine in Kettering,” follows this impulse-pandering into politics. Instead of political leadership, we now have politics led by focus groups. The public gets what it asks for (V-chips and populist slogans), not what it needs (healthcare and infrastructure improvements).

Freud himself is treated ambiguously in the documentary. Although he benefitted by his nephew’s promotion of his writing, one gathers he was uncomfortable with commercial exploitation of his ideas. Enigmatically, the final camera shot zooms in on Freud’s tombstone. Perhaps we are to imagine him turning over in his grave.

How can democracy work best, given that our choices are inevitably swayed by irrational unconscious forces? Curtis isn’t explicit, but implies that treating people as rational tends to make them moreso. Even as a firm believer in the dynamic unconscious, I find this a hopeful point of view. It also occurs to me that it is a researchable hypothesis, and that such research may in some measure counterbalance commercial and political profiteering from research on unconscious influence. The ethical implications of powerful social institutions exerting covert influence are only telegraphed in the documentary; they deserve a detailed analysis in their own right.

Century of the Self has engaging interviews, rare archival footage, a sweeping view of recent history, and, alas, somewhat irritating music. It was reviewed quite positively when it came out, and despite being over ten years old, still has a great deal to offer. I don’t wish to force anyone to watch it, but I do highly recommend it.

July 31st, 2013  Telepsychiatry is clinical evaluation and psychiatric treatment at a distance. It brings a specialist’s expertise to otherwise inaccessible populations in prisons, military settings, and distant rural communities. Introduced decades ago, it is perhaps the most successful example of the more general field of telemedicine. Telepsychiatry traditionally treats patients at supervised sites and makes use of secure, special-purpose video conferencing equipment. A number of companies offer technologies and services to facilitate telepsychiatry. The patients served by telepsychiatry often suffer significant mental illness, such that diagnosis tends to be based on overt signs and symptoms. Treatment is usually pharmacologic. Telepsychiatry is clinical evaluation and psychiatric treatment at a distance. It brings a specialist’s expertise to otherwise inaccessible populations in prisons, military settings, and distant rural communities. Introduced decades ago, it is perhaps the most successful example of the more general field of telemedicine. Telepsychiatry traditionally treats patients at supervised sites and makes use of secure, special-purpose video conferencing equipment. A number of companies offer technologies and services to facilitate telepsychiatry. The patients served by telepsychiatry often suffer significant mental illness, such that diagnosis tends to be based on overt signs and symptoms. Treatment is usually pharmacologic.

More recently, mental health blogs and articles have trumpeted the growth of online psychotherapy conducted by private-practice clinicians. While this falls under the rubric of telepsychiatry, it differs in important respects from traditional applications of this technology. Online psychotherapy is usually conducted as part of a private practice, without institutional oversight or standardization. The patient is typically at home or work, not in a supervised setting. Off-the-shelf consumer technologies such as Skype and FaceTime are often employed, potentially running afoul of HIPAA privacy regulations. And perhaps most crucially, the patients are higher functioning, with more subtle problems that demand nuanced discussion and finessed interventions.

The idea of conducting psychotherapy at a distance is not new. Sigmund Freud often corresponded with his patients in ways he hoped would be clinically helpful. Telephone sessions were pioneered in the 1960s with the advent of suicide hotlines, and have expanded to cover many area of mental health counseling. (See this 1993 discussion of telephone counseling by an attorney representing the California Association of Marriage and Family Therapists.) Psychotherapy by telephone remains extremely popular, often serving as a temporary substitute for in-person sessions, for crisis intervention between regular sessions, and to maintain a therapeutic relationship when one party moves out of the area. Despite the lack of visual cues, studies suggest that telephone psychotherapy and counseling are effective and liked by clients.

Early efforts to use the internet as a medium for psychotherapy seemed to take a step backward with text-only channels such as email or chat. In contrast to a phone conversation, text chatting hides vocal prosody and other paralinguistic features, obscuring irony, double-meanings, and similar subtleties. Email shares these shortcomings and is also asynchronous, i.e., the conversation does not occur in real time. Despite the severe limitations of a text-only exchange, early computer programs sparked the public’s imagination that someday the computer itself would conduct psychotherapy, and not simply facilitate communication between two humans. With the exception of highly structured cognitive and psychoeducational interventions, this has not yet been achieved.

Computer-mediated psychotherapy most commonly takes place online, over video conferencing apps such as Skype and FaceTime. These tools are readily available for free, and are easy to set up and use. Controversy exists over whether Skype and FaceTime are “HIPAA compliant,” although there is a strong argument that cellphone conversations with patients, not to mention unsecured email, are far more vulnerable to privacy breaches (Skype and FaceTime feeds are encrypted by default, whereas cellphone calls and email are not).

When the alternative is no psychotherapy at all, the utility of conducting it online seems obvious. Example scenarios include patients who are bedridden or otherwise immobile, those in inaccessible locations such as Antarctic explorers, and those who are immunocompromised or highly contagious with an infectious disease. Additionally, online therapy reasonably substitutes for telephone therapy in typical situations such as crisis intervention or when an existing therapy dyad is geographically separated, perhaps temporarily.

It is more potentially problematic to choose online therapy over in-person treatment when both are practical options. Certain patients, e.g., depressed or agoraphobic, may opt not to venture out of the house when it would be beneficial for them to do so. In-person treatment is inherently a social interaction, which may be therapeutic in itself — or at least good practice. Psychotherapy at a distance precludes smelling alcohol on the patient’s breath, as well as noticing auditory and visual subtleties such as a quiet sigh or dilated pupils. Micro-momentary facial expressions, implicated in unconscious interpersonal communication, may be overlooked. And to underscore the obvious, the therapeutic frame may be harder to maintain when the patient is in swimwear by the pool, and drinking an alcoholic beverage during the session. The potential for patient acting-out, including with suicidal threats or gestures, can render an online therapist especially helpless, and possibly more easily manipulated, than his or her counterpart in an office setting.

Online psychotherapy has practical advantages in some situations, and as a treatment modality it does not appear bogus or inherently harmful. It would be interesting to compare telephone and video therapy in a research context, to see whether the visual channel confers additional useful information, and whether it enhances or detracts from the therapeutic alliance. As with most technological innovations, online therapy also introduces new pitfalls and deepens old ones, so it is best not to choose it merely for its novelty or expedience. Face to face treatment is still the gold standard.

June 6th, 2013  As posted previously, last month I attended the American Psychiatric Association’s (APA’s) annual conference. Straying from my usual format, I thought I’d post pictures from the meeting and, of course, offer comments. The meeting took place in Moscone Center, a conference center complex located just south of Market Street in downtown San Francisco. Depicted here are anti-psychiatry protesters who held a rally in front of the main entrance at noon on the first day. There was also an exhibit of psychiatry’s cruelties (psychosurgery, shock treatment, inhumane conditions in asylums, etc) running all five days in a tent across the street from the conference. As posted previously, last month I attended the American Psychiatric Association’s (APA’s) annual conference. Straying from my usual format, I thought I’d post pictures from the meeting and, of course, offer comments. The meeting took place in Moscone Center, a conference center complex located just south of Market Street in downtown San Francisco. Depicted here are anti-psychiatry protesters who held a rally in front of the main entrance at noon on the first day. There was also an exhibit of psychiatry’s cruelties (psychosurgery, shock treatment, inhumane conditions in asylums, etc) running all five days in a tent across the street from the conference.

The conference was also a block from Yerba Buena Gardens, where I caught a very pleasant Balinese gamelan concert at the same time as the protest rally. This simultaneity — two events scheduled to coincide, forcing a choice — was a constant in the conference as well. The “scientific program” consisted of numerous overlapping talks, such that attending any presentation meant missing five or more other good ones. I’m not sure why the APA opted for such frustrating redundancy. Nor can I explain why predictably popular talks were scheduled into small rooms, with the result that dozens of registrants were turned away once the room filled. For instance, the crowd for Otto Kernberg’s psychoanalytic talk on love and aggression was several times larger than the assigned room. In this unusual case we were all moved to a cavernous hall at the last moment, where Dr. Kernberg gave a warm and very engaging presentation on the necessity and creative consequences of aggression in romantic love. (I like how this photo depicts the renowned psychoanalyst Kernberg representing the APA in an era of biological ascendancy.) In this unusual case we were all moved to a cavernous hall at the last moment, where Dr. Kernberg gave a warm and very engaging presentation on the necessity and creative consequences of aggression in romantic love. (I like how this photo depicts the renowned psychoanalyst Kernberg representing the APA in an era of biological ascendancy.)

The same huge auditorium was to hold the keynote address by Bill Clinton. However, Mr. Clinton was ill and could not be there in person. Several hundred (a couple thousand?) conference-goers nonetheless waited over an hour to see him on video. Mr. Clinton was pleasant, thoughtful, and charismatic, but didn’t offer much specifically about psychiatry or mental health. Mostly he spoke about public health needs in general. Mostly he spoke about public health needs in general.

I didn’t take many photos in the talks themselves. Officially it was forbidden, although this rule was routinely ignored by attendees. The quality of the presentations was high — I mostly chose “mainstream” ones this time, not the many off-beat and generally smaller meetings. I attended presentations on suicide, personality disorders, PTSD, sexual compulsions, DSM-5 and mood disorders, the controversy over antidepressant efficacy, psychiatrists writing and blogging for the general public, teaching psychotherapy to residents, and assessing the capacity of demented patients to make medical decisions for themselves. There were dozens of others I would have liked to attend, had they not coincided with the ones I chose.

I skipped the industry-sponsored, free lunch or dinner, non-CME presentations. But I did wander through the exhibit hall, both to see the “new investigator” scientific posters, and to peruse the brand-new DSM-5. In contrast to the last time I went to this conference, the industry booths seemed less garish and “over the top.” Of course, there were still a lot of them. Several had raffles where valuable prizes such as an iPad Mini could be won by those who gave the company their contact information. One booth offered a pocket digest of the new DSM-5, MSRP about $60, to everyone who watched a 12 minute presentation and coughed up a mailing address. I was tempted… but no. (It’s interesting to ponder how much a single psychiatrist contact is worth to a drug company. Much more than $60, I’d venture.) Of course, there were still a lot of them. Several had raffles where valuable prizes such as an iPad Mini could be won by those who gave the company their contact information. One booth offered a pocket digest of the new DSM-5, MSRP about $60, to everyone who watched a 12 minute presentation and coughed up a mailing address. I was tempted… but no. (It’s interesting to ponder how much a single psychiatrist contact is worth to a drug company. Much more than $60, I’d venture.)

The DSM-5 itself is $200 in hardcover, $150 in paperback — an unabashed moneymaker for the APA. Despite the incredible controversy it stirred up, my impression is that the changes from DSM-IV-TR are relatively minor. In particular, the personality disorder section hasn’t changed much, although the new edition is no longer multi-axial, i.e., there is no “Axis 2”. Some language has been made more precise, as well as more “biological” in some passages, and some disorders have been expanded to include more that would previously have been considered normal. Whether this is good or bad depends on one’s perspective in several respects; mostly I find it unfortunate. DSM classifications often matter more to insurers and disability officers than to practicing psychiatrists, who in David Brooks’ words are “heroes of uncertainty” (echoing an earlier post of mine, but I’ll forgive him for not quoting me). We deal with individuals, not disease categories.

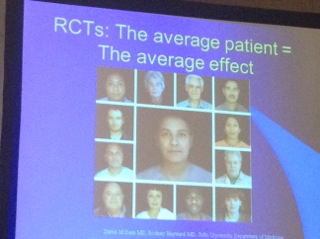

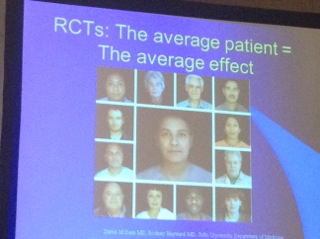

I will end with a slide from the talk on antidepressant efficacy that summarizes this tension in my field. As I’ve discussed previously, randomized controlled trials (RCTs) are the gold standard for scientific rigor in psychiatry; however, a lot of psychiatry is not scientific in this sense. DSM categories help define the “average” patient with a particular disorder, leaving a lot of wiggle room since the categories are not based on etiology. RCTs say which treatments best help this “average” patient, represented by the computer composite in the center of this slide. However, I don’t see “average” patients, I see one of the 12 individuals who contributed to the composite. Thus, for me, the new DSM was a sideshow at the conference. The most insightful presentations, whether on PTSD, suicide, or capacity assessment, combined science and the nuanced human communication of meaning. They recognized that our work is informed by science but goes well beyond it. Anti-psychiatrists don’t like this, insurers don’t like this, neuroscientists don’t like this, even many psychiatrists don’t like this. But it’s true and inevitable for the foreseeable future. I like it. As for the APA annual meeting, I’m glad I went, and equally glad I won’t feel the need to go back for several years at least.

May 8th, 2013  In my last post, I outlined the fundamental problem facing advocates of nonviolence: Despite nearly universal conceptual agreement with this goal, human psychology conspires to make peace elusive and strife apparently unavoidable. Our emotions trump our rationality, biasing assessments of real-world evidence and leading to post-hoc justification of whatever our “gut” feels. Unfortunately, and rightly or wrongly, our gut feels scared or mistreated much of the time. Violence is often the result, whether construed as self-defense or justified retribution. This occurs with individuals, groups, and nations, and behaviorally ranges from brief verbal expressions of contempt to weapons of mass destruction and genocide. In my last post, I outlined the fundamental problem facing advocates of nonviolence: Despite nearly universal conceptual agreement with this goal, human psychology conspires to make peace elusive and strife apparently unavoidable. Our emotions trump our rationality, biasing assessments of real-world evidence and leading to post-hoc justification of whatever our “gut” feels. Unfortunately, and rightly or wrongly, our gut feels scared or mistreated much of the time. Violence is often the result, whether construed as self-defense or justified retribution. This occurs with individuals, groups, and nations, and behaviorally ranges from brief verbal expressions of contempt to weapons of mass destruction and genocide.

Gut reactions cannot be overcome by rational argument alone. “Fight or flight” responses to threat, and urges to inflict retribution or punishment, start at the emotional level. Since it is unrealistic to hope for a world without emotional triggers — without perceived threats that “demand” violent self-defense, or injustice that “demands” violent retribution — those who advocate nonviolence must accept the reality of emotional provocation. Another reality is that even those who endorse a nonviolent philosophy are saddled with the same emotional reactivity as everyone else. Given these constraints, how can nonviolence be promoted an emotional level?

Safety

It has often been said that our physiologic response to stress serves us well in situations for which it was originally designed, e.g., an attack by a wild animal, but that it is misplaced in our modern world of “attacks” by time deadlines, career pressures, and miscommunication by loved ones. Autonomic stress responses — increased pulse and blood pressure, outpouring of stress hormones, faster reaction time — may save our lives in dire situations, but only hurt and exhaust us when activated chronically and without purpose. Many effective ways of managing unhealthy stress do so by enhancing feelings of safety and relaxation, emotions that are incompatible with the stress response.

In many respects, violence is similar. With rare exceptions, it is a reaction to a perceived threat. It may be said that violence serves us in situations “for which it was originally designed”: self-defense against a warring enemy or a criminal intent on killing us. Yet it only hurts and exhausts us individually and as a species when activated chronically. Enhancing feelings of safety and relaxation helps us be less violent and more peaceful; conversely, a heightened sense of danger and tension promotes violence. While dangerous threats exist in the real world, they trigger violence emotionally, not rationally. Being cut off in traffic may constitute a real physical threat, but our urge to respond with verbal or physical violence arises from a complex stew of imagined contempt by the other, anonymity in our vehicle, an assessment of the likelihood of further escalation, how much we feel they “deserve” it, and similar factors. Emotional safety is complex and not easily assured. Yet it is a necessary element in our closest relationships, in our work, in our communities, and on the world stage. When it is lacking, violence often results.

Humanization of the Other

This is perhaps better stated in the negative: It takes dehumanization to commit violence. From schoolyard putdowns to racial epithets to “the enemy” in wartime, our thoughts and language serve to make emotionally driven violence acceptable. It is hard to treat another person as expendable or deserving to suffer while imagining his or her grieving parents or children — so we take pains not to. Seeing each other as cherished, capable of suffering, and harboring a unique view of the world — in a word, human — is another necessary element for promoting nonviolence. Without it, people are means to an end, not ends in themselves.

Role Models

Depicted with the prior post was Mahatma Gandhi, the first to apply nonviolent principles to politics on a large scale. Gandhi’s nonviolent philosophy, which he termed satyagraha, would likely have had little influence without his personal actions and role-modeling that led to political change in India and elsewhere. Gandhi modeled nonviolence working. Role models such as Gandhi, Martin Luther King, Jr., and Jesus of Nazareth show others a peaceful path by modeling not only behavior, but also emotion: the courage to act according to ideals, without succumbing to fear that might otherwise justify violence.

A similar role model is depicted with this post. Morihei Ueshiba (often called O Sensei, or Great Teacher) founded the Japanese martial art of aikido. Based on earlier violent styles, aikido aims to neutralize violent attack while leaving the attacker unharmed. Aikido’s core principle of harmonizing one’s physical and spiritual energy with the attacker’s would be little more than esoteric philosophy if not for its practical application. As Gandhi did in politics, Ueshiba modeled nonviolence working, in this case against literal physical attack, and in a manner that can be learned and practiced by others.

Early Learning

Patterns of emotional reactivity are established in early childhood. While a propensity to violence may be inborn, nonviolent alternatives can be introduced quite early as well. A society dedicated to nonviolence would teach this in preschool, introducing more sophisticated and challenging scenarios in grade school and beyond. Such a curriculum would not pretend that the world is a peaceful place. Maintaining a nonviolent stance in a world that seems to demand the opposite is a lifelong challenge. All the more reason to start confronting this challenge as soon as possible, ideally before personality is codified and harder to influence.

Practice

It’s one thing to aspire to an ideal, quite another to behave accordingly. There is no substitute for practice, “walking the walk” as well as “talking the talk.” Emotion may trump rationality, but intentional action (and well-chosen cognitions) can shape emotion. Practicing peaceful conflict resolution may occur in daily life, of course. But in addition, dedicated training or exercises may be necessary elements. For example, disciplined participation in nonviolent political action, or in aikido training, may instill peaceful “reflexes” in a way that merely hearing or reading about these practices cannot.

In this post I outlined ways of promoting nonviolence, taking into account emotional and worldly realities. This list is very general and far from exhaustive, and is offered in the spirit of collaboration and discussion. Instead of dividing ourselves by tactics — more guns laws or fewer? death penalty or not? — common ground seems a better place to start. Most of us seek peace, yet most of us share emotions that feed violence. This makes a peaceful world an elusive yet worthy goal we can work toward together.

April 25th, 2013  Prompted by the Sandy Hook shootings and Boston Marathon bombings, a bumper crop of articles about our violent society has sprouted in recent weeks. I was particularly drawn to this opinion piece in the New York Times. Author Todd May, a Clemson University professor of Humanities, articulates well the crucial underpinning of a nonviolent world view: “the recognition of others as fellow human beings, even when they are our adversaries.” Drawing on the philosophy of Immanuel Kant, who said that the core of morality lay in treating others not simply as means but also as ends in themselves, May argues that the key to a nonviolent society is “to see our fellow human beings as precisely that: fellows. They need not be friends, but they must be counted as worthy of our respect, bearers of dignity in their own right.” Prompted by the Sandy Hook shootings and Boston Marathon bombings, a bumper crop of articles about our violent society has sprouted in recent weeks. I was particularly drawn to this opinion piece in the New York Times. Author Todd May, a Clemson University professor of Humanities, articulates well the crucial underpinning of a nonviolent world view: “the recognition of others as fellow human beings, even when they are our adversaries.” Drawing on the philosophy of Immanuel Kant, who said that the core of morality lay in treating others not simply as means but also as ends in themselves, May argues that the key to a nonviolent society is “to see our fellow human beings as precisely that: fellows. They need not be friends, but they must be counted as worthy of our respect, bearers of dignity in their own right.”

May is surely correct about this. A morality based in respect for others, and in recognition of our duties and obligations to others, underlies most of the defensible arguments favoring nonviolence. (The major alternative, a utilitarian morality based on outcomes and consequences, will forever argue that the ends justify the means, even if the means are violent.) The Golden Rule “do unto others…” and biblical admonitions to “love thy neighbor as thyself” are based on this type of reasoning, called Kantian or deontological.

At the philosophical level, then, the challenge is to convince ourselves and each other that deontological respect for our fellow human beings is itself a concept worthy of respect. To put it mildly, this is not so easy. Everyone from Confucius to Jesus to Gandhi has tried. Yet “peace on earth, goodwill to men” still sounds like a pipe dream, lovely words that have no bearing on real life. Even the many of us who claim to accept this precept often act otherwise. Why does this perspective, favored by virtually all world religions — as well as secular humanists — and argued most compellingly by our greatest thinkers, nonetheless fail to gain traction? The answer to this central question of human existence: psychology.

Sadly, we humans don’t always behave sensibly. Our feelings often precede and even dictate our thoughts. This was first brought home to me when, as a college student witnessing a political protest, I suddenly realized that the emotional fervor expressed by both sides had very little to do with thinking the issue through. Indeed, it seemed people who understood the subject the least had the strongest feelings about it, pro or con. Moreover, it appeared that people become emotionally invested first, and only later bolster their positions with post-hoc reasoning. Around the same time, I helped with a well-known psychology experiment on confirmation bias, our human tendency to grant greater weight to evidence that supports what we already believe. In the experiment, subjects who already had strong opinions pro or con about the death penalty reviewed exactly balanced “evidence” — I should know, I fabricated it — and reached opposite conclusions. That is, both sides felt more justified in their prior belief by weighing more heavily that portion of the evidence that agreed with their existing position. Those already in favor of the death penalty became more in favor, those already opposed became more opposed. Both the political rally and this experiment figured centrally in my decision to pursue a mental health career. Here was proof that people simply aren’t rational — and that’s fascinating.

While fascinating, this reality bodes poorly for reasoned arguments aimed to influence others. As a society we argue endlessly over social issues: the role of government, whether private gun ownership increases or decreases one’s safety, the legitimacy of gay marriage, how we should treat undocumented immigrants. Selected (i.e., biased) facts, statistics, and images are lobbed back and forth. Those who already agree with a particular bias applaud; those who are opposed become annoyed and counter with facts, statistics, and images of their own. For the most part, everyone feels vindicated by their confirmation bias. Very few minds are changed.

Nonviolence is an especially poignant case. Nearly everyone claims to be on the side of discouraging and decreasing violence, yet there is vehement disagreement over how to achieve this. Moral directives to “do unto others” or “love thy neighbor” are dismissed as naive. Here in the real world it’s “peace through strength,” “the best defense is a strong offense,” and “a pacifist is someone who hasn’t been mugged yet.” Violence is treated emotionally as axiomatic, a given, with post-hoc justification that “they deserve it” or “they started it,” or that committing violence now prevents more later. It is a necessary evil, an entrenched part of the human condition.

In part two, I will pick up from here. Given that moral reasoning alone rarely changes anything or anybody in the real world, what can? Is there a meaningful way to promote nonviolence?

March 24th, 2013  The annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association (APA) is in San Francisco this May. I’ve attended twice before as I recall, both times when it was here. I enjoyed it, and even felt it was worth the $1000 we non-members pay to get in, although in my opinion it’s not worth doubling that for airfare and lodging to attend in another city. The presentations were generally of high quality, and so plentiful that I always found something worthwhile to attend. Up to 50 CME (continuing medical education) hours are available over five days, enough to maintain a California medical license for two years. This year, in addition to the other presentations, the new DSM-5 will be unveiled and discussed, so we can anticipate hearing a lot that is new and essential for clinical practice. Bill Clinton will give the keynote speech. The annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association (APA) is in San Francisco this May. I’ve attended twice before as I recall, both times when it was here. I enjoyed it, and even felt it was worth the $1000 we non-members pay to get in, although in my opinion it’s not worth doubling that for airfare and lodging to attend in another city. The presentations were generally of high quality, and so plentiful that I always found something worthwhile to attend. Up to 50 CME (continuing medical education) hours are available over five days, enough to maintain a California medical license for two years. This year, in addition to the other presentations, the new DSM-5 will be unveiled and discussed, so we can anticipate hearing a lot that is new and essential for clinical practice. Bill Clinton will give the keynote speech.

Yet it’s a hard decision for me to attend this meeting. The APA and its annual meeting reflect aspects of psychiatry that concern me. In 2006 the drug industry accounted for about 30 percent of APA’s $62.5 million in financing, half through drug advertisements in its journals and meeting exhibits, and the other half sponsoring fellowships, conferences, and industry symposia at the annual meeting. Every year the annual meeting features a huge exhibit hall of lavish booths courtesy of the pharmaceutical industry. In past years I watched my fellow psychiatrists line up for branded coffee mugs and similar swag; although voluntary restrictions by the Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America (PhRMA) in recent years have curtailed this, the APA itself welcomes such giveaways according to this year’s information sheet for exhibitors. This year there are industry sponsored “Product Theater” presentations most days around lunchtime (six sessions total, up to 250 attendees per session), and “Therapeutic Update” meetings at dinnertime (three two-hour sessions) — pure marketing vehicles that are not approved for CME, that lack any pretense of scientific balance or neutrality, and that come with a nice free meal to tickle the limbic systems of the recipients. In fact, there’s a surprisingly wide range of promotional and marketing opportunities at the meeting (pdf here) that the APA sells to industry. We participants may sign up for the scientific presentations and collegiality, but the APA invites us for the millions of dollars we bring in.

Of course, individual attendees aren’t forced to take a seat at a “Therapeutic Update” and may never set foot in the exhibit hall. So what’s the problem? Can’t attendees enjoy an educational experience free of commercial influence? Unfortunately, with APA selling everything from sponsored wi-fi, to plasma-screen billboard space, to branded do-not-disturb signs at the hotel, the industry flavor will be hard to miss. Registrants are warned that our names, titles, mailing addresses, and email addresses will be “shared” (i.e., sold) to meeting exhibitors. Perhaps there’s an unpublicized opt-out I’m not aware of.

Whatever one thinks of this blizzard of advertising to a highly selected, captive audience of over 10,000 psychiatrists, it hardly needs to be said that the practice of psychotherapy will have no deep-pocketed sponsorship; healthy nutrition, exercise, lifestyle balance, and introspection will enjoy no “Product Theater” or “Therapeutic Update.” If this year’s meeting resembles those I attended in the past, many presenters will mention the importance of psychosocial factors in mental health, and, if one seeks them out, there will be talks by some of the luminaries in trauma research and psychological treatments. But this will be in the context of blaring signs promoting the newest antidepressant, mood stabilizer, and anti-psychotic — which nowadays may all be the same product — and a zeitgeist of DSM diagnoses leading to pharmaceutical remedies.

Speaking of DSM, the unveiling of DSM-5 ought to be interesting. DSM diagnosis is an integral part of most mental health (not just psychiatric) practice, as treatment authorization and reimbursement by health plans often hinge on the DSM disorder for which the patient “meets criteria.” Both the process of creating the new DSM-5 and its conclusions have come under repeated attack from a range of reputable critics, including the chair of the DSM-IV Task Force Dr. Allen Frances, Division 32 of the American Psychological Association (the “other” APA), the British Psychological Society, the American Counseling Association, and others. One common criticism is that diagnostic categories are being loosened (or widened), such that more patents will meet criteria for a mental disorder, and in turn more psychiatric medications will be prescribed. Dr. Frances charges that the APA treats publication of DSM-5 as a “cash cow,” citing the hefty cost ($199 hardcover, $149 paperback) of this instant and inevitable best-seller. My own feelings about the DSM are mixed, and I’m curious to see how the newest edition turned out, particularly the section on personality disorders.

Despite my concern about undue commercial influence, misplaced priorities, and its controversial diagnostic manual, I plan to go to the APA meeting this year. There’s too much of value to me in all those presentations. But when I pass the anti-psychiatry protesters at the entrance, I know I will wish for some way to declare myself neither anti-psychiatry nor, despite appearances, in full agreement with the spectacle within.

February 15th, 2013  There comes a time, fairly early in many psychotherapies, when there is nothing left to talk about. The identified problems have been named and discussed, there is no more need to bring the therapist up to speed on one’s history. In essence, the patient’s conscious agenda for coming to therapy has been exhausted. I tell trainees this often happens around session #7 — truly it’s more variable than that — when the patient has voiced all his or her prepared topics, said everything already known or consciously felt about the issues, and offered all the background he or she believes is relevant. The patient may then appeal to the therapist for guidance, not in any profound sense, but simply to suggest something to talk about, so they don’t sit there in awkward silence. There comes a time, fairly early in many psychotherapies, when there is nothing left to talk about. The identified problems have been named and discussed, there is no more need to bring the therapist up to speed on one’s history. In essence, the patient’s conscious agenda for coming to therapy has been exhausted. I tell trainees this often happens around session #7 — truly it’s more variable than that — when the patient has voiced all his or her prepared topics, said everything already known or consciously felt about the issues, and offered all the background he or she believes is relevant. The patient may then appeal to the therapist for guidance, not in any profound sense, but simply to suggest something to talk about, so they don’t sit there in awkward silence.

A dynamic therapist typically turns this back on the hapless patient: “Say anything that comes to mind.” This challenge can bring therapy to a grinding halt — or trigger the start of genuine exploration. For it is only when the patient speaks unrehearsed and without self-censorship, in the moment, that the two can observe the here-and-now workings of the patient’s mind. It has been mere preamble up to this point, groundwork at best and chit-chat at worst, not the real work of dynamic psychotherapy. Speaking “without a script” allows topics to arise that are impolite, uncomfortable, and awkward, ideas the patient previously thought but chose not to say, feelings that had been brushed aside up to that point. Some patients unfortunately cannot speak without a script; it is too scary and they are too defensive. Dynamic therapy ends at that point, although emotional support and cognitive techniques may still prove very helpful. But for those with the courage to look at themselves, their own defenses, resistance, and unconscious motivation, it’s time to dive in and explore the unknown.

In a similar vein, patients at any stage of treatment sometimes arrive to a session with nothing to discuss that day. They exude an uncharacteristic blandness or boredom, as if to signal: “Nothing to see here, just move along.” With a mildly apologetic tone they claim to have no burning issues, nothing especially vexing or troubling. In fact, maybe it’s time to talk about wrapping up treatment…

If this presentation stands in contrast to the patient’s usual enthusiasm, I take it as a very good sign. Something emotionally important is going on, and the patient’s Unconscious is trying desperately to throw us off the trail. In the language of dynamic therapy, this is resistance: unconscious effort to avoid painful or troubling material in therapy. Some patients employ this sort of resistance constantly, and for this reason are either very challenging to treat, or they “vote with their feet” and leave treatment early in the process. But when a new resistance stands in clear contrast to the patient’s typical openness, it is easier for the therapist to recognize it, easier to point it out to the patient (who is more open to hearing about it), and easier to identify dynamics that may underlie it.

In my experience, these unusually boring or bland openings lead, more often than not, to the best sessions. Because the patient is not consciously avoiding a troubling issue, and because I rarely know at first what motivates the patient’s avoidance that day, it becomes a shared exploration where new discoveries and insights come to light. For reasons I can’t quite explain, the factors motivating such resistance are not deeply buried or inaccessible. They usually become apparent to both of us well within the 50-minute hour. “Making the unconscious conscious” (in Freud’s famous words) leads the patient to new and unexpected insights — usually a delightful experience for us both — and also to clearing of the leaden resistance, which is no longer needed to keep the material out of consciousness. Rather than heralding the end of the treatment, awkward silence at the start of an hour, like the awkwardness near the start of many a dynamic psychotherapy, points the way to important thoughts and feelings. It turns out there is a lot to talk about.

|

|