March 8th, 2014  A patient I see for psychotherapy, without medications except for an occasional lorazepam (tranquilizer of the benzodiazepine class), told me his prior psychiatrist declared him grossly undermedicated in one of their early sessions, and had quickly prescribed two or three daily drugs for depression and anxiety. He shared this story with a smile, as we’ve never discussed adding medication to his productive weekly sessions that focus on anxiety and interpersonal conflicts. Indeed, the lorazepam is left over from his prior doctor. I doubt I would have ordered it myself, although I don’t particularly object that he still uses it now and then. A patient I see for psychotherapy, without medications except for an occasional lorazepam (tranquilizer of the benzodiazepine class), told me his prior psychiatrist declared him grossly undermedicated in one of their early sessions, and had quickly prescribed two or three daily drugs for depression and anxiety. He shared this story with a smile, as we’ve never discussed adding medication to his productive weekly sessions that focus on anxiety and interpersonal conflicts. Indeed, the lorazepam is left over from his prior doctor. I doubt I would have ordered it myself, although I don’t particularly object that he still uses it now and then.

Of course, there’s a completely innocuous way to explain this difference between his prior psychiatrist and me. My patient could have looked much worse back then, in dire need of pharmaceutical relief. However, he didn’t relate it to me that way, and I have no reason to doubt him. There’s also the possibility that I’m missing serious pathology in my patient — that I too would urge him to take medication if only I recognized what I’m now overlooking. But… I don’t think so. I’m left to conclude that his prior psychiatrist and I evaluated essentially the same presentation rather differently.

In particular, I’m struck by the term “undermedicated” (more often spelled without the hyphen, according to my Google search). This judgment most often comes up in speaking about populations, as in the debate over whether antidepressants are over-prescribed or under-prescribed in society at large, or whether children are diagnosed with ADHD and prescribed stimulants too often, or not often enough. Under- and overmedication are also commonly mentioned when describing medication management of pain, a thyroid condition, mania, or chronic psychosis in an individual. Here the terms express disagreement with a particular dosage, where the benefits of treatment and adverse side-effects or risks are deemed out of balance one way or the other.

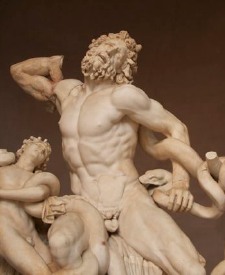

“Undermedicated” also implies that adding medication is the preferred or only sensible treatment approach. While this may always be true in hypothyroidism, it clearly isn’t with regard to physical or emotional pain. The term rhetorically denies non-medication alternatives. I would also add that, to my ear, “overmedicated” and especially “undermedicated” sound dehumanizing, as though referring to a machine that is out of adjustment, or a chemical solution being titrated on a lab bench. Since the natural state of human beings is not to be medicated at all, it sounds a bit odd to hear someone — as opposed to one’s disease — assessed this way. Perhaps I am especially sensitized to this after reading a controversial article by Moncrieff and Cohen that highlights the “altered state” induced by psychotropics and their lack of known, specific mechanisms of action. There is often a supposition that medication dosage correlates with symptom relief. This is not always true of subjective states, underscoring that the complexity of human experience often belies simple “over/under” judgments.

My patient’s mood and anxiety vary with his interpersonal situation. It wouldn’t occur to me to turn his “thermostat” up or down in general, even if drugs reliably could do this. Yet I know colleagues who’d argue that one, two, or even three daily medications could help him overcome his everyday challenges of dealing with people. These approaches point to different fundamental viewpoints in psychiatry. Does the patient have a disease, an as-yet-undiscovered chemical (or electrical, viral, inflammatory, etc) imbalance in the brain that is best remedied by a medical intervention, accurately dosed neither “over” nor “under”? In acute mania or florid psychosis, as in hypothyroidism, it seems to me the answer may be yes, although this is unproven and time will tell. Perhaps, too, in severe melancholic depression. But in social anxiety? Self-consciousness? Feeling discouraged about one’s career? The field’s perspective on these has shifted in recent decades, such that now a hidden biological cause is assumed by default, or at least held out as a rationale for treatment. It is only by making this dubious assumption that one can speak of undermedicating such complaints, or the people who have them.

January 24th, 2014  Over on the Shrink Rap blog I got caught up in an off-topic debate. The post was on why psychiatrists avoid insurance panels, something I’ve written about myself. But the commentary wandered into exorbitant fees, inadequate mental health services for the poor, income disparity between psychiatrists and patients, a generation that expects something for nothing, and so on. After a week, prompted by minor irritation with San Francisco’s transit system the night before, I finally posted a comment. I wrote that buses and taxicabs perform roughly the same service, but for many riders who can afford it, a cab is worth the extra money. I acknowledged that the analogy to mental health care was flawed: bus and cab fares are both regulated, and psychiatric care is often more urgent and critical, and definitely more expensive, than an optional ride downtown. Nonetheless, the comparison made the point that more affordable mental health services are inevitably “bus-like,” and that there is a legitimate role for higher-cost “taxi-like” services for those willing and able to pay for them. Over on the Shrink Rap blog I got caught up in an off-topic debate. The post was on why psychiatrists avoid insurance panels, something I’ve written about myself. But the commentary wandered into exorbitant fees, inadequate mental health services for the poor, income disparity between psychiatrists and patients, a generation that expects something for nothing, and so on. After a week, prompted by minor irritation with San Francisco’s transit system the night before, I finally posted a comment. I wrote that buses and taxicabs perform roughly the same service, but for many riders who can afford it, a cab is worth the extra money. I acknowledged that the analogy to mental health care was flawed: bus and cab fares are both regulated, and psychiatric care is often more urgent and critical, and definitely more expensive, than an optional ride downtown. Nonetheless, the comparison made the point that more affordable mental health services are inevitably “bus-like,” and that there is a legitimate role for higher-cost “taxi-like” services for those willing and able to pay for them.

It’s important to realize that all analogies are flawed. They only highlight certain similarities between two situations. There will always be differences too, the salience of which are inevitably disputed by partisan debaters. For this reason analogies illustrate far better than they convince. One commenter noted that even “bus-like” mental health services are not always available. A psychiatrist pointed out that many of us accept reduced fees or otherwise “come to some agreement” with cash-strapped patients in ways taxi drivers don’t. Then another commenter who frequently writes about forced psychiatric treatment argued that coercion never occurs with buses or cabs, rendering my analogy “shallow at best.”

Going off-topic, I replied that forced treatment, e.g., being subjected to a 72-hour legal hold (the “5150” here in California), is uncommon in office psychiatry, and in any case didn’t bear on the point I made. I later added that a number of non-psychiatrists are also authorized to apply the 5150 in California, and in many instances would be far more likely to do so than a psychiatrist in a private office. My interlocutor, and at least two others, pressed on: the mere possibility, however remote, of being placed on a legal hold is a threat that evokes fear in current and potential patients. This fear keeps some who “truly need psychiatric intervention … from even attempting to access ‘help’.”

I had already let it drop when our host asked everyone to return to the topic of insurance panels. But it’s a point that bears discussion, here if not there. Do patients avoid office psychiatrists for fear of being placed on a legal hold?

I’m sure the answer is yes, at least sometimes. In the first place, many patients do not know what triggers a 5150. Movies, popular culture (such as the depicted t-shirt), and history itself prime the public to think a padded cell readily follows from a few ill-chosen words. Often I’ve reassured patients that ideas or feelings, however destructive or horrific, never in themselves lead to involuntary commitment. Patients are free to divulge fantasies of mass murder, elaborate suicide scenarios, gruesome torture, etc. without risk of being locked up. Indeed, talking in confidence about disturbing ideas or feelings is a good way to defuse their emotional power.

But there’s much more to this than simply not knowing the law. In my experience a great many patients fail to distinguish feelings and actions. They try unsuccessfully to control troubling feelings, and somehow equate this with uncontrolled behavior, a very different thing. Yet the distinction is hugely important in life, and with regard to legal holds. Feelings never justify a hold, whereas behavior, or its “probable” likelihood, does. If this distinction is unclear, even feelings seem dangerous.

At a more subtle level, patients with hostile or self-destructive feelings often expect to be punished for them, or they unconsciously feel guilty, i.e., that they should be punished. Indeed, people avoid psychotherapists of all types, imagining the therapist will condemn or humiliate them for the ugliness of their inner world. Unconscious mixed feelings, i.e., simultaneously fearing and seeking a harsh response, are common as well. A crucial part of dynamic psychotherapy is gradually trusting that the therapist won’t fulfill this fantasy. Seeing a psychiatrist evokes these usual fears of being judged and punished, heightened in some by the psychiatrist’s power to diagnose and to initiate a legal hold — even if the risk of the latter is virtually zero.

I hasten to add that we psychiatrists don’t make this any easier for ourselves or our patients when we are sloppy about applying legal holds. Patients’ fears of subjectivity and loose criteria are partly based in reality. A casual “better safe than sorry” attitude may send the wrong message, trampling the treatment alliance and savaging trust. Meticulous care in applying the 5150 is a “frame issue” as central to therapeutic success as any other treatment boundary. As a profession we can never count on being afforded more trust than we have earned (and sadly, often less).

Of course, there are circumstances when we rightly apply a legal hold in the office. A patient who believably voices, or behaviorally telegraphs, intent to die or to kill others should expect a trip to the psychiatric ER for further evaluation in a secure setting. Conversely, there are presumably people intent on suicide or homicide who consciously avoid seeing psychiatrists who could thwart their plans, just as they avoid telling their family or the local police. Such people, however, are not seeking psychiatric assistance to avoid dying or killing. If they were, they would accept help, including inpatient treatment if needed.

I once had a patient who came to see me, he said, so I could convince him not to die. If I failed, he would kill himself. I quickly replied that I wouldn’t play this game, although I was more than willing to talk with him about his suicidal feelings. We met five or six times; he wasn’t truly interested in overcoming suicidal feelings, and I wouldn’t engage in the no-win challenge he set up. He left — no hold applied — and months later I learned he was still very much alive.

Similarly, those who rail against the completely predictable response of psychiatrists to voiced threats of harm are enacting a “death by cop” scenario. The paradigm is someone who brandishes a weapon in front of police, who then react the only way they can — and usually with great regret. Fantasies of punitive authority, forcing the hand of those in power, and/or getting one’s just desserts, are made real. Patients who force their psychiatrists to take control of their behavior likewise sacrifice adult autonomy in order to enact a primitive unconscious fantasy. Unlike most patients who are relieved to be protected from their own frightening impulses, these few harbor antagonisms that may feel more vital to them than life itself.

December 31st, 2013  I grew up in the era of the nuclear arms standoff. Thousands of warheads on land, at sea, and in planes stood ready to obliterate most of the human race if the Soviets, Americans, or a rogue third nation launched a nuclear “first strike.” Authors of that era wrote of the psychological effects of living under such a threat (not that it is gone now, but it certainly felt different back then). Some said it rendered life fundamentally meaningless. Why indulge personal hopes or dreams when we, our community, our entire culture could be gone in an instant? Psychiatrist Robert Jay Lifton coined the term “psychic numbing” for the denial we employed, individually and collectively, to allow us to live our lives while faced with the real and ever-present risk that our world might end that very day. I grew up in the era of the nuclear arms standoff. Thousands of warheads on land, at sea, and in planes stood ready to obliterate most of the human race if the Soviets, Americans, or a rogue third nation launched a nuclear “first strike.” Authors of that era wrote of the psychological effects of living under such a threat (not that it is gone now, but it certainly felt different back then). Some said it rendered life fundamentally meaningless. Why indulge personal hopes or dreams when we, our community, our entire culture could be gone in an instant? Psychiatrist Robert Jay Lifton coined the term “psychic numbing” for the denial we employed, individually and collectively, to allow us to live our lives while faced with the real and ever-present risk that our world might end that very day.

Psychic numbing was curious yet undeniable. We all knew the danger was real. But because the unimaginable horror of World War Three was coupled with an apparent inability to do anything about it, we told ourselves the likelihood was low and somehow pushed it aside. Instead of being the top priority it arguably should have been, nuclear annihilation lurked like an ominous cloud at the periphery of consciousness. We and our comedians made nervous jokes about it. A few idealists joined peace and disarmament groups. Meanwhile, the rest of us watched warily out of the corner of our eye, weighed down by a pervading fatalism and learned helplessness.

The dynamic of psychic numbing is repeating itself today. This time it is not the existential risk of nuclear war, but the reality of losing our privacy. Revelations that our own government monitors our private telephone conversations and tracks our vehicles, allegations that a few years ago would have been waved off as paranoid rantings, are now headline news. We now know that our email is scrutinized for keywords (and possibly collected and stored in its entirety), and our cellphones are used to track our locations. Like the nuclear threat of the 1970s, it feels as if we can’t do anything about it. Our discomfort lurks like an ominous cloud at the periphery of consciousness. We and our comedians make nervous jokes about the NSA. A few idealists join activist groups to oppose the scrutiny of innocent citizens. Meanwhile, the rest of us watch warily out of the corner of our eye, weighed down by a pervading fatalism and learned helplessness.

The theft of privacy has been opportunistic and widespread. The 9/11 terrorist attack justified not only “security theater” at airports, but also a trading away of everyday privacy in the name of national security. Video cameras monitor public areas in major cities; license plates of highway traffic are scanned en masse and recorded by local and state police; the FBI can activate your laptop’s webcam remotely and secretly (with a court order). Meanwhile, quite apart from national security or law enforcement considerations, internet privacy has become an oxymoron. The social web, an aspect of Web 2.0, promoted living one’s life in full view of “friends” and others. Facebook and Twitter distribute micro-doses of fame to monetize the formerly private lives of their users. Younger people post photos of themselves in compromising situations while failing to appreciate the permanence of these images. Older people use online health and mental health support sites, not realizing their “private” conversations are archived and publicly searchable. A great many advertisers and others track web activity for commercial purposes, amassing huge databases without users’ knowledge or consent. Whether on actual highways or the quaintly-named information superhighway, the distinction between public and private is quickly eroding away.

Is privacy passé, a luxury we can no longer afford? Psychic numbing tells us to shrug and bear the new reality. As many thought 30 or 40 years ago about the nuclear arms race, loss of privacy appears to be the price of living in our modern world.

Don’t believe it. The forces that now seek to strip us of individuality and dignity have always been here. New technologies present novel challenges, but human nature hasn’t changed. It took decades to realize we weren’t forced to live with Mutual Assured Destruction hanging over our heads. When we overcome our psychic numbing this time, we will re-discover that nervous humor, wary sidelong glances, and helpless fatalism are not effective ways to deal with a real problem. We will re-discover the value and honor in self-respect.

December 12th, 2013  My fellow psychiatrist and blogger Dinah Miller raised this simple yet profound question on Shrink Rap the other day. Who is rightfully labeled mentally ill? Is it anyone with a psychiatric diagnosis, past or present? Anyone with currently active psychiatric symptoms? Anyone receiving psychiatric treatment? Dr. Miller observes that “the mentally ill” is an oft-cited demographic. It carries much social weight — negative in the form of discriminatory practices related to employment, driving, and gun ownership, and positive in the form of entitlements, disability status, and the like. With so much riding on this label, knowing exactly how and to whom it applies seems crucial. My fellow psychiatrist and blogger Dinah Miller raised this simple yet profound question on Shrink Rap the other day. Who is rightfully labeled mentally ill? Is it anyone with a psychiatric diagnosis, past or present? Anyone with currently active psychiatric symptoms? Anyone receiving psychiatric treatment? Dr. Miller observes that “the mentally ill” is an oft-cited demographic. It carries much social weight — negative in the form of discriminatory practices related to employment, driving, and gun ownership, and positive in the form of entitlements, disability status, and the like. With so much riding on this label, knowing exactly how and to whom it applies seems crucial.

“But there is no agreed upon definition of who is mentally ill, and the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM) lists hundreds of disorders, limiting its utility as the determinant of who is mentally ill and therefore eligible for discrimination, stigmatization, or special benefits…. I’m a psychiatrist, and I confess, I have no idea who these ‘mentally ill’ are.”

She includes a brief survey that she hopes everyone — mental health professionals, patients, and neither/both — will fill out. At this point, if you’d like to complete her survey before I bias you with my own thoughts, go ahead and do that, then come back here.

Ok, here is my view of “the mentally ill.” It’s a term I’ve never felt comfortable with, and thus rarely use, owing to what I view as imprecision. Certain groups define mental illness to suit their purposes. For example, the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI) declares that “mental illness is a medical condition,” and then provides a list of selected mental disorders they believe qualify as “mental illness.” This in turn leads to the rather incredible claim that “one in four adults… experiences mental illness in a given year. ” However, NAMI’s definition does not reflect common usage, nor does it comport with the way “illness” is used in the rest of medicine. More commonly, mental illness is a conceptually slippery, undefined euphemism that makes it easier to talk about restricting the rights of a subpopulation, or conferring benefits on them, without being too specific about whose rights are affected and why.

Definitions can be descriptive or prescriptive. The former is how a word or phrase is actually used, the latter how it is properly used. In actual use, “mentally ill” seems most often to mean manifesting a severe, observable psychiatric condition that renders the person unable to live normally. Florid psychosis, mania, and severe obsessive-compulsive symptoms are clear examples. However, contrary to NAMI, even fairly severe depression is equivocal, and neurotic anxiety, mild depression, and most personality disorders are clear non-examples. Typical discourse around rights and entitlements conflates current mental illness with high likelihood of having mental illness in the near future. So a person can be temporarily free of impairment and yet still be subject to the restrictions and entitlements of someone in the throes of impairment.

As mentioned, this is not how “illness” is used in the rest of medicine. (I’m about to get prescriptive here.) Medical anthropologists long ago differentiated disease (or diagnosis) from illness. The former may be asymptomatic and completely unknown to the patient. Examples include the “silent killer” hypertension and an asymptomatic brain tumor. In contrast, illness is a subjective state of feeling medically unwell, plus the psychological, social, and cultural consequences of this state. Those suffering a cold, “the flu,” or nausea feel ill, even if the exact underlying disease is not well characterized. Illness leads to a socially defined “sick role”: the ill person is relieved of his or her usual duties, accepts help from caregivers, is more needy and less autonomous than usual, etc. If “mental illness” were used the way “illness” is used in the rest of medicine, ego-syntonic conditions, e.g., most mania, would be termed disorders but not illnesses. Conversely, mild to moderate depression and anxiety would be unequivocal mental or emotional illnesses, even lacking a specific diagnosis.

Since “mentally ill” obscures as much as it clarifies, perhaps no one should be labeled this way. Indeed, only in psychiatry can a person be declared ill by someone else. In the rest of medicine, it’s self-descriptive. In my view, “the mentally ill” harbors too many unstated implications and vaguely shared assumptions regarding whom we are talking about. Legal restrictions and entitlements should be based on more concrete standards — and actually, they are. “Mental illness” is more of a rhetorical flourish, a bit of hand-waving when it’s difficult or inconvenient to pin down specifics.

November 11th, 2013  In my last post I outlined some complexities of third party payment for office psychiatry, and especially for psychotherapy. As my example I used Medicare, the only third party payer I bill. Some of the problems include complex billing (i.e., collecting from multiple parties), partial reimbursement, unrealistic documentation requirements, loss of patient confidentiality, and a misplaced emphasis on medication “evaluation and management” over psychotherapy. There are also challenges specific to dynamic psychotherapy, such as obscuring the transference. But I saved the most fundamental issue for this post: Does third party payment for psychotherapy make sense in general? In my last post I outlined some complexities of third party payment for office psychiatry, and especially for psychotherapy. As my example I used Medicare, the only third party payer I bill. Some of the problems include complex billing (i.e., collecting from multiple parties), partial reimbursement, unrealistic documentation requirements, loss of patient confidentiality, and a misplaced emphasis on medication “evaluation and management” over psychotherapy. There are also challenges specific to dynamic psychotherapy, such as obscuring the transference. But I saved the most fundamental issue for this post: Does third party payment for psychotherapy make sense in general?

This may seem a puzzling question, coming from me. I not only value deeply what psychotherapy offers, I make my living from it. Shouldn’t it go without saying that psychotherapy should be paid for somehow, no matter where the money comes from? My experience with public and private health insurers tells me otherwise.

“Medical necessity” is the linchpin, and frankly the problem. The more a therapeutic encounter fits a medical model and is arguably “necessary” in that framework, the more readily it is covered by health insurance. Psychotherapists of all stripes tiptoe uncomfortably around this issue. Medication management fits the medical model very well, so psychiatrists who incorporate this into their psychotherapy sessions enjoy outsized reimbursement (or their patients do). Talking about anything else, no matter how central to the patient’s presentation, does not fit the medical model nearly as well. Nonetheless, psychotherapists who offer a step-by-step approach aimed concretely at relief of symptoms emulate medical evaluation and treatment much more than those who employ open-ended, exploratory approaches to tackle dysfunctional family dynamics, chronic self-sabotage, and many other concerns for which people seek psychotherapy (and later report benefit; see Consumer Reports, November 1995, Mental health: Does therapy help? pp. 734-739, and this analysis of the Consumer Reports survey by Martin Seligman). Note that the crucial variable for coverage is not what helps more, or relieves more agonizing misery. It’s what seems more “medical.”

Using “medical necessity” as the criterion to treat human misery that often isn’t medical at all leads to much inconsistency and even cruelty. As mentioned in my last post, insurers demand that I code my “procedure” (i.e., the session) depending on what we talked about. If we spend the hour discussing medications, even if this focus can easily be understood as a symbolic, unconscious appeal by the patient for care-taking or some other emotional need, it’s worth far more to the insurer than if we spend the same hour explicitly discussing the patient’s experiences and reactions to actual caretakers. (As added irony, the latter discussion can obviate the former in future sessions, a detail lost on insurers and most everyone else.) Since private insurance partly reimburses many of my non-Medicare patients based on how their sessions are coded, an agitated, marginally employed, chronically suicidal patient with severe personality issues is reimbursed far less over time than a high-functioning, stably-employed patient with a medication obsession. This makes no sense and is blatantly unfair.

The truth is, I’m the same expert — and put bluntly, worth the same amount of money — no matter what I’m discussing with the patient. That is, as long as I have the integrity to focus on the patient’s central issues, not to provide or bill for unneeded services, not to offer hand-waving in lieu of explanation, not to mindlessly prescribe medication after medication, not to casually chat and call it psychotherapy, and so forth. In other words, I need to be a good doctor instead of a sloppy or unethical one. I need to know when to be “medical” and when not to be.

Traditional dynamic psychotherapy fits the medical model especially poorly. It is not primarily focused on symptom relief. The treatment is not tailored to diagnostic categories. It follows no step-by-step sequence. Even expert practitioners often cannot estimate treatment duration. After many decades of published studies the evidence base for treatment efficacy still triggers heated debates. Arguing “medical necessity” for such treatment is at best unnatural, at worst contrived or even misleading. (It’s even more absurd to argue the medical necessity of one specific session in an ongoing treatment; to me, this is like asking whether the 10th note in a piano concerto is “musically necessary.”) Those of us who recognize the value of dynamic work and have seen patients change in important, fundamental ways are kept busy trying to pound this square peg into a round hole. But CBT doesn’t avoid this problem either: it’s more like a square peg with rounded corners.

Faced with the struggle to show medical necessity, it’s tempting to wonder whether psychotherapists should refuse to play this game. However, opting out isn’t easy. Even if I chose not to be a Medicare provider — I admitted my mixed feelings about this last time — self-pay patients with private insurance would still seek maximal reimbursement for seeing me. I can hardly blame them. I see no way out of participating, at least indirectly, in this misapplied standard of medical necessity.

It’s hard enough to assure that all Americans have access to basic health care. Assuring that all have access to mental health care is one step harder, even when that care accrues only to the seriously mentally ill and fits the medical model very well. It will be a very long time indeed before America deems it worthwhile to offer psychotherapy to the so-called worried well: those who have all their faculties but are miserable due to inner conflicts, self-defeating beliefs, or a traumatic past. If that day ever comes, it will be when medical necessity is supplanted by a more fitting standard, one that judges mental distress and its treatment on their own merits, and not by borrowing legitimacy from medicine.

October 31st, 2013  From late 1996 to early 2007 I was medical director of a low-fee mental health clinic where psychiatry residents and psychology interns receive training. Since the clinic accepted Medicare for payment, I did as well. I signed on as a Medicare “preferred provider” and have remained on the panel ever since, even though I left the clinic for full-time private practice nearly seven years ago. From late 1996 to early 2007 I was medical director of a low-fee mental health clinic where psychiatry residents and psychology interns receive training. Since the clinic accepted Medicare for payment, I did as well. I signed on as a Medicare “preferred provider” and have remained on the panel ever since, even though I left the clinic for full-time private practice nearly seven years ago.

I never joined private insurance panels for several reasons. As an inveterate do-it-yourselfer, I’ve always handled my own billing and bookkeeping. This is considerably harder when multiple health plans are billed, co-payments collected, and so on. I like the straightforward way I provide a service, and the person receiving the service pays me directly. Somehow it feels more honest than contracting with health plans to funnel referrals my way. Private health plans also pay less than usual-and-customary fees and require doctors to share patients’ private details with corporate reviewers to document “medical necessity.” Moreover, since dynamic psychotherapy has always been a big part of my practice — increasingly so over time — I’m sensitive to arguments that third-party payment complicates transference and countertransference, obscures acting-out around payment, and detrimentally takes payment out of the treatment frame. Last but not least, as I’ll discuss mainly in my next post, insurers base reimbursement on a medical model that fits poorly with dynamic work.

The upshot is that I have a cash-only (or “self pay”) practice, with the exception of my Medicare patients. Until this year, Medicare “allowed” 65% or so of my full fee. (Medicare sets an allowed fee for a given service, and then pays 50-80% of that. I can collect the rest, up to the allowed amount, from a secondary insurer or from the patient. This works more or less automatically for secondary insurers, and rather awkwardly when I try to collect from patients.) In 2013 the CPT codes for psychiatric office visits were revamped. This made billing more complicated, and introduced odd, often illogical variations in Medicare and private insurance reimbursement — sometimes paying more than before, sometimes less.

As one of the few private-practice, office-based psychiatrists in San Francisco still on the Medicare panel, I’ve become a magnet for these patients. A local medical center with which I have no affiliation used to refer several callers to me every week, until I sent a letter asking them to please not kill me with their kindness. Medicare callers request to see me for medications only, even after I explain this is not the nature of my practice. It’s more tricky when patients claim to want therapy to get a foot in the door, and then once in my office and now my medico-legal responsibility, confess that they only wanted medication refills all along. Some callers ask to be added to a non-existent waiting list, or to call me every month or two to see if I change my mind about accepting them as patients. Clearly, the demand is there, the economic incentive is not.

Medicare and other third-party payers have a valid need to assure their money isn’t wasted. Sometimes my claims are rejected, as when I received a notice this week that one patient’s diagnosis (Depression Not Otherwise Specified, 311) “is inconsistent with the procedures” I billed (three weekly sessions of moderate-complexity medication management, 99213, combined with 50-minute therapy sessions, 90836). It’s tempting to protest this, as there’s absolutely nothing inconsistent about treating atypical depression with medication and psychotherapy. I could take the time to marshal my arguments, compose a letter, and reveal personal details about my patient to present my case. But it’s far easier to resubmit the claim with a slightly upcoded diagnosis, e.g., Major Depression, recurrent, mild severity, 296.31, and get paid. This uncomfortably clashes with my usual tendency to downcode slightly to protect my patient’s confidentiality. (Since pressures to upcode and downcode routinely distort the documentation of diagnoses in clinical practice, I’m skeptical of all research that uses these diagnoses to derive conclusions about psychiatric practices, disorder incidence, and the like. Garbage in, garbage out.)

Upcoding and downcoding in such cases is not criminal mischief, but an attempt to fit traditional, mainstream psychiatry into a procrustean bed of medical-model diagnosis and procedure coding. Public and private insurers alike sacrifice ecological validity for documentation that appears, but really isn’t, “evidence based.” To take one example, as of this year we must code medication “evaluation and management” separately from the provision of psychotherapy, even if in practice these are done simultaneously and inseparably. A 50-minute psychotherapy session (90836) that includes brief attention to medication (99212) is reimbursed at a much lower rate than the same 50-minute session with more time devoted to meds (99213 or 99214). This makes little sense when in many cases the psychotherapy is far more clinically significant than the medications being discussed. (You’ll note that I think of the psychotherapy code first, but actually it is an add-on to the primary medication “E & M” code.) If medications are not mentioned or evaluated at all, there is yet another code to use for psychotherapy (90834), with an “allowed fee” of $89 for 50 minutes, well below what any psychiatrist or psychologist actually charges. If this isn’t bewildering enough, some of my colleagues are now doing 52-minute sessions, an insignificant increase in duration that qualifies for a different code with much higher reimbursement.

Since cash-only practice excludes all but the affluent, I view my taking Medicare as a modest concession to avoid elitism. I also support a single-payer health care system, also known as “Medicare for all,” so participating in Medicare feels like practicing what I preach. At the same time, it’s easy to see why most of my office-based colleagues opt out of Medicare: lower pay for more paperwork, rules that don’t make sense, and various factors that make dynamic psychotherapy harder to conduct and be paid for. So far I still answer yes, albeit hesitantly, when asked whether I take Medicare. In my next post I’ll expand these ideas into private insurance for outpatient psychiatry, including whether dynamic psychotherapy resembles a medical intervention enough to fit a “medical necessity” model.

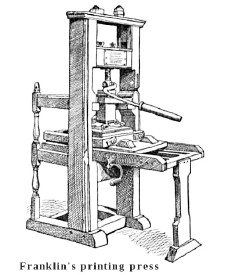

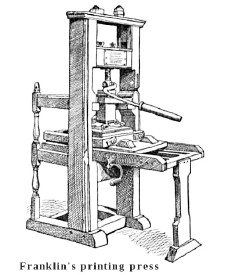

September 29th, 2013  A central disruptive technology of our online world is the breaking down of unidirectional communication. In years past, newspapers and other media published articles without immediate feedback from readers. True, a few readers might telephone the editor’s desk, and the paper might print a select handful of “letters to the editor” in the next issue. But by and large: “Freedom of the press is guaranteed only to those who own one” (A.J. Liebling, The New Yorker, May 14, 1960). The average person didn’t own a printing press. A central disruptive technology of our online world is the breaking down of unidirectional communication. In years past, newspapers and other media published articles without immediate feedback from readers. True, a few readers might telephone the editor’s desk, and the paper might print a select handful of “letters to the editor” in the next issue. But by and large: “Freedom of the press is guaranteed only to those who own one” (A.J. Liebling, The New Yorker, May 14, 1960). The average person didn’t own a printing press.

Now, thanks to blogs, online forums, e-books and the like, anyone can publish. There is freedom of the press for the masses, but not necessarily an audience. The ubiquitous comments section in online media thus has a special place in the publishing ecosystem. Eyeballs are attracted to the professional publication, meanwhile public commentary hangs on its coattails, gaining readership it would not otherwise enjoy.

My local newspaper, the San Francisco Chronicle, has a free online version. The prolific public commentary is loosely moderated: some comments are deleted for personal attacks, obscenity, and the like. Nonetheless, an air of bravado, vigilantism, and snap judgment weaves through page after page of commentary. For example, an unfolding story about a fatal knifing following a baseball game attracts scores of comments with each new revelation. Readers decide the young men are “thugs,” argue over who likely started the fight, declare sports fans crazy and San Francisco as way too soft on crime. Some proclaim with certainty that self-defense justifies wielding a knife, others just as adamantly that it never does. There are 145 such comments today, adding to those from yesterday.

Does freedom to express an offhand opinion, and the privilege of having it seen by thousands of others, contribute to public discourse? On the one hand, a freewheeling marketplace of ideas arguably allows the best to prevail. Unfettered competition among different ideas, like competing products in a marketplace (or competing species in biological evolution) leads to survival of the fittest. Neighbors discussing issues of mutual concern over the proverbial backyard fence — isn’t this a cornerstone of democracy?

Popular Science takes a different view. The 141 year old publication this week announced it is ending online comments on its articles. They say a barrage of commentary that rejects well-established science, e.g., evolution and global climate change, creates controversy where none legitimately exists. They claim this serves neither science nor the society that depends on it. The announcement cites a Mother Jones piece that profiles and interviews a climate-change denying “troll”; notably, the 370 comments following that article run the gamut from thoughtful points about climate change to a heated debate about “mens’ rights activists” and “femi-nazis” that has nothing to do with the original post.

Meanwhile, back at the San Francisco Chronicle website, a column appeared last week about a young man with apparent psychiatric issues who “is proof that something isn’t working with the mental health care system.” He was picked up five times in recent months for bizarre, minor crimes — punching cars, climbing street signs, stripping naked in public, etc. Each time he was detained on a 72-hour psychiatric hold, after which he was released. Most recently he was atop a 40 foot ledge for nine hours, screaming and threatening passersby and police, all of which tied up dozens of first-responders, snarled traffic, and cost the city a lot of money. As a result he is now in the County Jail medical ward, booked on an array of felony and misdemeanor charges.

The 97 comments that follow this column largely decry this man’s repeated, rapid release from psychiatric custody. Here are a few excerpts:

• We need to get the laws in this country changed to make it possible to put people like this in longer-term hospitalization.

• Seriously what about some sanity, if your getting picked up repeatedly by the cops you need to be on long term hold.

• So basically some lucky person has to be injured or killed by this guy before anything will be done.

• Bring back psych hospitals. The pendulum has swung too far to an extreme in allowing the mentally ill to put themselves, and society, at risk on the streets. The social experiment has failed.

A few ideas quickly occurred to me. We don’t apply psychiatric holds based on how much “trouble” people stir up. He’s apparently not holdable — if he were, he would have been held. Maybe he clears quickly, as would be the case with a medical cause of bizarre behavior, or drug intoxication. He’s detained on criminal charges now, so he won’t be released in 72 hours this time unless he posts bail. But the main thing that occurred to me is how this commentary so glaringly contrasts with that on the psychiatry blogs I read. In these latter, narrow-focus forums, the predominant tone of the commentary is anti-psychiatric. No one argues for longer-term hospitalization or says the pendulum has swung too far in favor of patients’ rights.

Obviously, this is a matter of readership. For better or worse, Chronicle readers feel safer with psychiatrists than they do with the man in the news story, and they aren’t terribly sensitive about protecting the latter’s liberty. Anti-psychiatrists, in contrast, are a small but vocal minority who disproportionately flock to psychiatry blogs, just as those who reject science flock to the comment boards at Popular Science. Some of the blogs at Psychology Today also attract devoted critics, some of whom hotly object to the tone with which a sensitive topic has been discussed. (My blog is apparently not controversial enough to attract such vitriol.) Should psychiatrist bloggers and those at Psychology Today follow the lead of Popular Science? Should we disallow commentary, claiming that it creates controversy where none legitimately exists, and that this false controversy serves neither our professional work nor the society that depends on it?

In my view, the answer is captured by a variation of the Yerkes-Dodson law. That is, too little agreement is just as bad as too much. An echo chamber of unanimity brings conversation to a halt, as does a cage fight where everything offered is criticized in a hostile way. Discourse proceeds best when all parties and views are treated with respect, and when a substantial shared basis for discussion exists. In my opinion, commentary should be permitted on online forums. However, comments that reject the basic tenets of the discussion — the legitimacy of science in a science forum, mental health treatment in a psychiatry or psychology forum — should be disallowed. Speakers have a right to express such views, of course, just not by usurping the forums and readership of their opponents. Likewise, off-topic comments, whether commercial spam, political diatribes, or pet peeves, do not add to thoughtful discourse. Nor does overt contempt or name-calling. This means comment moderation is needed, which adds effort and expense to operating an online media outlet. But the situation as it is now does not serve public discourse very well. Freedom of speech is not the freedom to grab the microphone from the speaker’s hand and use it to shout to a crowd who came to hear someone else.

|

|

A patient I see for psychotherapy, without medications except for an occasional lorazepam (tranquilizer of the benzodiazepine class), told me his prior psychiatrist declared him grossly undermedicated in one of their early sessions, and had quickly prescribed two or three daily drugs for depression and anxiety. He shared this story with a smile, as we’ve never discussed adding medication to his productive weekly sessions that focus on anxiety and interpersonal conflicts. Indeed, the lorazepam is left over from his prior doctor. I doubt I would have ordered it myself, although I don’t particularly object that he still uses it now and then.

A patient I see for psychotherapy, without medications except for an occasional lorazepam (tranquilizer of the benzodiazepine class), told me his prior psychiatrist declared him grossly undermedicated in one of their early sessions, and had quickly prescribed two or three daily drugs for depression and anxiety. He shared this story with a smile, as we’ve never discussed adding medication to his productive weekly sessions that focus on anxiety and interpersonal conflicts. Indeed, the lorazepam is left over from his prior doctor. I doubt I would have ordered it myself, although I don’t particularly object that he still uses it now and then.