January 14th, 2013  A patient of mine recently observed that the increasing use of the the term “psychopath” in popular media is really a disguised way of criticizing selfishness. Dressing up selfishness as an odd and frightening clinical disorder — slapping a diagnostic label on it — makes for catchy news copy, and grants pundits emotional distance between themselves and those monsters who look just like us, but who lack the empathy and remorse that make us human. A patient of mine recently observed that the increasing use of the the term “psychopath” in popular media is really a disguised way of criticizing selfishness. Dressing up selfishness as an odd and frightening clinical disorder — slapping a diagnostic label on it — makes for catchy news copy, and grants pundits emotional distance between themselves and those monsters who look just like us, but who lack the empathy and remorse that make us human.

I immediately thought of how narcissism had its heyday in popular culture very recently as well, and to similar ends. Narcissists and psychopaths care only about themselves, and have no qualms about hurting and sacrificing others when it suits their purposes. These are dangerous people lurking among us; all the more reason to publish lightweight magazine and newspaper pieces on how to spot them in the wild.

Both labels sound like psychiatric diagnoses, but actually they’re not. According to Heinz Kohut and other theorists, narcissism is a quality everyone has to a greater or lesser degree. It normally develops in infancy: the sense all babies have that the world revolves around them. However, we gradually learn that we are not the center of the world, and that other people, including our primary caregivers, have their own goals and perspectives separate from our own. Infantile narcissism is thus tempered by the reality of healthy relationships, although its vestiges are present in our self-pride, and perhaps in our proven tendency to overestimate our own efficacy and performance. Pathological narcissism in this view is infantile normality carried abnormally into adulthood. It only becomes a psychiatric diagnosis when the condition fulfills certain observable criteria and impairs social and/or occupational functioning. Likewise, psychopathy is a personality trait, not a diagnosis. Renowned psychopathy researcher Robert Hare notes that “psychopathy is dimensional (i.e., more or less), not categorical (i.e., either or).” DSM-IV doesn’t include a diagnosis called “psychopathy” or “sociopathy.” Instead, there is antisocial personality disorder, which overlaps with psychopathy but is not the same thing.

These terms, psychopath and narcissist, are loosely applied personality labels when popularized in the media. What do they add over simply calling someone callous or selfish? First, they offer an explanation — a pseudo-explanation really — of frightening and/or mystifying behavior. Our feeling of powerlessness is eased by the label, as though now that the threat is identified, we may be able to do something about it. Second, such labels imply that misbehavior is a function of one’s character, a categorical determination. Yet categorical psychiatric diagnosis, especially of personality, is controversial in general. Moreover, we often overestimate personality factors and underestimate situational ones (the “fundamental attribution error“) in explaining the behavior of others. Using a label like psychopath or narcissist to describe another person (whom we’ve only heard about in the news, and haven’t formally evaluated) reaches for a premature conclusion about the cause of that person’s behavior. In a way, we are falsely reassured.

Third, the label adds power to our verbal disapproval. We have a long history of abusing psychiatric labels in the service of putting others down. Consider “idiot,” “moron,” and “imbecile,” all originally coined as official categories describing low IQ. Or “cretin,” which originally referred to physical and mental disability due to congenital thyroid deficiency. Or the casual use of “crazy” and its synonyms. Some patient advocates argue further that any diagnostic label used as a noun is demeaning, i.e., calling someone a schizophrenic, a neurotic, a borderline, etc. Instead, it is more respectful to refer to a person (or patient) who has schizophrenia, or a narcissistic personality. But that’s exactly the point of the popular use of terms like psychopath and narcissist: To show disrespect and disdain, to disapprove. And to underscore the difference between ourselves and the person with the label.

Our earliest social categories are “good guys” and “bad guys,” defining one against the other. From “cops and robbers,” to team sports, to bipartisan politics, to our allies and foes on the world stage, we divide self and other at every level, calling the former good and the latter bad. Callousness and selfishness are in all of us to some degree, and it hurts to admit it; it damages our self-image. Instead, we psychologically defend against this realization in ourselves by projecting these traits onto others using a broad brush and pejorative terms. While some people truly are unusually callous or selfish, the popular use of scientific-sounding labels serves our own psychological needs by identifying “bad guys” and making us feel better about ourselves.

December 30th, 2012  A person is drunk or angry or momentarily distraught. Or all three. He or she takes an overdose or cuts a wrist, then reconsiders — or never intended to die in the first place — and either calls 911 or tells someone else who calls 911. The police come and transport the person to a psychiatric emergency service where a three-day legal hold is placed. Despite expressing regret for the suicide attempt, the person is admitted for observation and safekeeping. A person is drunk or angry or momentarily distraught. Or all three. He or she takes an overdose or cuts a wrist, then reconsiders — or never intended to die in the first place — and either calls 911 or tells someone else who calls 911. The police come and transport the person to a psychiatric emergency service where a three-day legal hold is placed. Despite expressing regret for the suicide attempt, the person is admitted for observation and safekeeping.

I sometimes question the clinical utility of short-term psychiatric hospitalization for regretted suicide attempts. Not that it’s always wrong, of course, but sometimes it seems to result from sloppy thinking. The usual rationale is that it’s better to be on the safe side. I.e., if the person’s recent words or actions cast doubt on his or her wish to be alive, it’s better not to take chances. This has merit in cases where there’s some honest doubt: Since our statistical success in predicting dangerousness to others and to oneself is quite limited, “false positives” are the price we pay (well, they pay) to keep the “true positives” safe.

But another reason seems even more pervasive though less often stated: Hospitalization is a predictable and presumably undesired consequence of expressing suicidal feelings. At one level, legal holds and involuntary hospitalization “train” patients not to express suicidal feelings, lest they spend three or more days in an expensive inpatient unit with its attendant shame, stigma, and many inconvenient rules and expectations. It may also serve a related function of taking the patient seriously. Big consequences follow big actions, real or contemplated, and in this way discourage the patient from “upping the ante” with a more serious suicide attempt.

The other side of the coin is that legal holds and hospitalization make us feel better. We’re taking action, not just sitting there. Clinical management is clear-cut for a change. We have an interesting little story with heroic overtones to tell our colleagues. The treatment plan is easy to justify to third-party payors, unlike more subtle interpersonal interventions. (A few days ago I was on the phone with a managed care reviewer who demanded a “5-axis diagnosis” and behavioral treatment plan for my dynamic psychotherapy patient. A more pointless exercise I cannot imagine, except that my patient won’t receive insurance reimbursement without it. This level of skeptical scrutiny rarely arises in hospitalizing the suicidal, even though the cost to the payor is far greater and the benefits sometimes less apparent.) We’re hardly ever faulted for choosing to hospitalize.

Of course, this propensity to “hospitalize first and ask questions later” can backfire. I recall several times in my residency when homeless veterans came to the VA emergency room with bags packed, seeking psychiatric admission. Their claims of suicidal feelings — or even command hallucinations to commit suicide — were hard to argue with, even though it seemed obvious that the real goal was room and board, not psychiatric care. Their complaints quickly disappeared once admission was assured. At the time I noted that civil commitment laws exist to protect the unwilling and undeserving from being hospitalized; none address those who strive to be hospitalized without a valid reason.

A great many suicide attempts and gestures are communicative in nature. Far from being unambivalent decisions to die, they are cries for help, expressions of rage, tests of whether anyone really cares. Our responses as mental health professionals are communicative too. Hospitalization can say, “I’m not playing your game of manipulative suicide threats — I’m calling your bluff.” It can say, “I hear you, and I take your suicide threat very seriously. It’s my job to keep you safe.” It can say, “I blindly follow the rules. You say suicide, I call 911.” Conversely, choosing not to hospitalize can say, “I’m not playing into your drama of getting me to overreact,” or “I’m not taking you seriously, not hearing your pain,” or “I defy the conventions of my profession, you cannot count on me to hospitalize you.”

It’s important to pay attention to the message in one’s clinical actions, and also to realize that one’s message can be communicated in different ways. Hospitalization is not the only way to convey serious concern, even if at times it may be the only way to assure physical safety. If calling the police is an angry reaction to the patient’s misbehavior, it should be re-thought. Nor should it be an unthinking, reflexive response. The converse is true as well: If inaction is an expression of angry avoidance, denial of the severity of the patient’s risk, or a reflexive expression of the practitioner’s bold, iconoclastic nature, that too should be re-thought.

Failure to consider the risks and benefits (pros and cons) of hospitalization on a case-by-case basis would be evidence of sloppy thinking in psychiatric practice. While it may be less common than other forms of sloppy thinking I’ve posted about, it still happens disappointingly often. I also wanted to post about it to give readers a place to comment and ask questions about legal holds, as there is ongoing interest and concern on this topic.

Photo courtesy of Petr Kratochvil.

November 26th, 2012  I just read a mildly disturbing article in the New York Times called “What Brand Is Your Therapist?” The author Lori Gottlieb was a full-time journalist who took six years to retrain as a psychotherapist — her website, but not the article, says she has a master’s degree in clinical psychology. Yet she found herself virtually unemployed after several months and in search of marketing consultants to attract clients. The thrust of the article is that such marketing involves branding, i.e., defining a niche that promises quick, painless, easily grasped results, and then promoting oneself online and elsewhere using that brand. I just read a mildly disturbing article in the New York Times called “What Brand Is Your Therapist?” The author Lori Gottlieb was a full-time journalist who took six years to retrain as a psychotherapist — her website, but not the article, says she has a master’s degree in clinical psychology. Yet she found herself virtually unemployed after several months and in search of marketing consultants to attract clients. The thrust of the article is that such marketing involves branding, i.e., defining a niche that promises quick, painless, easily grasped results, and then promoting oneself online and elsewhere using that brand.

Gottlieb is clearly uncomfortable about the trade-offs inherent in branding and marketing psychotherapy services. Traditional psychotherapy is often painstaking, uncomfortable, and lengthy, and thus hard to sell. In contrast, one-time phone consultations and executive coaching are brief, feel-good interventions that lend themselves to snappy, positive catchphrases that sell better. Such services may be “fast-food therapy — something that feels good but isn’t as good for you; something palatable without a lot of substance.” Moreover, she notes that many sales techniques clash with the tenets of traditional psychodynamic therapy. Sharing personal details makes one more approachable and “human,” at the cost of complicating and possibly precluding transference work. Active use of social media such as Facebook and Twitter can attract potential clients and publicize one’s “brand,” but may also blur relationship boundaries essential for effective psychotherapy. Gottlieb lays out the dilemmas well in her article, but her practice website illustrates the practical conclusion: Lots of “selling” of various services, few of which are recognizable as psychotherapy.

Of course, I am writing this on my psychiatry blog, which is linked to my own practice website. I too have grappled with similar trade-offs. I launched my website over five years ago, and started the blog about a year later. Several months ago I heeded marketing advice I found online: I re-wrote my website in the first-person and added photographs. I expanded the sections on my hospital committee work and past research. I included more practical information about my practice.

Like Gottlieb, I had mixed feelings about doing this. On the one hand, helping potential patients make more informed choices sounds innocuous enough. I want suffering people to be able to find me and to know what I can help with. I want the process of engaging in psychotherapy to be as transparent as possible. I explain what I do, and even list my fees on my website (most of my peers don’t).

On the other hand, I’m concerned that branding and marketing commodifies a personal healing relationship. It offers to treat psychological issues in little bite-sized pieces, misleadingly suggesting that therapy to resolve one’s indecision about marrying, say, can be completely separate and distinct from therapy to deal with career indecision. It conflates psychotherapy with counseling and coaching, all of which are useful but different things. Mainly it risks dumbing down psychotherapy. Psychotherapy is often complex if done carefully, and in my opinion it can’t be conducted as well over the phone, by email, while sitting by the pool with Skype running on one’s laptop, or in a guaranteed four-session package.

I haven’t availed myself of the whole branding arsenal, since I strive to maintain a psychotherapy practice worthy of the name. If I ever write a book, offer coaching services, or engage in public speaking, those activities will be clearly distinct from my role as a psychotherapy-oriented psychiatrist. Moreover, patients and would-be patients seem to agree that informational websites are useful, but that too much branding and self-promotion by a psychotherapist is a turn-off. That makes good sense, and encourages me to take another look at my own website — I may turn it down a little. What do you think?

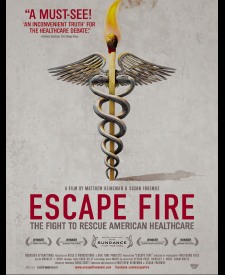

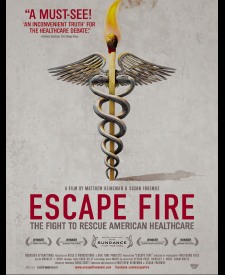

October 21st, 2012  The independent documentary Escape Fire: The Fight to Rescue American Healthcare by Matthew Heineman and Susan Froemke is a thoughtful indictment of the status quo. Instead of focusing on political polarization, the pros and cons of Obamacare for instance, the film mainly documents the absurdity and waste of what we have now. Instead of a system to promote health, Americans have a “disease management system” that spends almost twice as much as any other country — and nearly as much on prescription medicines as the rest of the world combined — yet we are 50th in life expectancy, and almost 75% of healthcare costs are spent on preventable diseases that are the major causes of disability and death in our society. Economic incentives maintain this status quo. High-tech interventions are reimbursed generously, yet reimbursement for face-to-face primary care often does not even cover the cost to deliver it. As a result, fewer new physicians enter primary care, and doctor visits become shorter and shorter. Meanwhile, unnecessary medical and surgical procedures are prevalent despite their risks, and cost thousands of lives each year. The independent documentary Escape Fire: The Fight to Rescue American Healthcare by Matthew Heineman and Susan Froemke is a thoughtful indictment of the status quo. Instead of focusing on political polarization, the pros and cons of Obamacare for instance, the film mainly documents the absurdity and waste of what we have now. Instead of a system to promote health, Americans have a “disease management system” that spends almost twice as much as any other country — and nearly as much on prescription medicines as the rest of the world combined — yet we are 50th in life expectancy, and almost 75% of healthcare costs are spent on preventable diseases that are the major causes of disability and death in our society. Economic incentives maintain this status quo. High-tech interventions are reimbursed generously, yet reimbursement for face-to-face primary care often does not even cover the cost to deliver it. As a result, fewer new physicians enter primary care, and doctor visits become shorter and shorter. Meanwhile, unnecessary medical and surgical procedures are prevalent despite their risks, and cost thousands of lives each year.

Escape Fire uses a firefighting metaphor to make its main point. In forest fires, sometimes a smaller fire is set in order to deprive the main fire of fuel, creating a firebreak. Such firebreaks can allow firefighters to escape the area — thus an “escape fire.” The filmmakers use this metaphor to say that the status quo in health care isn’t working, and that we may need counter-intuitive and non-traditional solutions to save the system. I confess that I find this metaphor somewhat ill-chosen: The remedies suggested in the film do not “fight fire with fire.” And there is no escaping our need to address health care.

The film spends much time on the military, in part as a microcosm of the problems facing our larger society. Soldiers’ use of prescription drugs has tripled in the past five years. A large section of Escape Fire, including fascinating footage inside a C-17 Medevac plane as it crosses the Atlantic, follows Sergeant Robert Yates returning from Afghanistan. Severely injured in a battle that killed most of his platoon, he suffers chronic pain and PTSD. Sgt. Yates was given a shopping bag full of pills, but later replaces them with stress- and pain-management techniques he learns as part of an innovative Army program.

Although the film never mentions psychiatry as a medical specialty, mental health issues loom large in both military and civilian health care. Again and again, patients are depicted in primary care offices reviewing their antidepressant medications, or breaking down in tears. The current system, devoted to disease management, offers poor care to such patients. They need time, not reimbursed procedures. As medical journalist Shannon Brownlee notes on camera: “Health care should have a lot more care in it.”

The film proposes several escape fires, i.e., solutions, to rescue American health care. In 2005 Safeway began to provide financial incentives for employees who engage in healthier behavior, and thereby lowered its health care costs by more than 40%. (That’s how the film puts it. Actually, from 2005 to 2009 Safeway’s health care costs remained flat for the 30,000 employees enrolled in the program, while most companies’ costs rose by 40% over the same period.) This was the one example of a monied interest realigning financial incentives to promote health. The film would have been stronger with more such examples — I hope there are some.

The military provides a solution of a different type. Often innovation gains a foothold there before achieving acceptance in civilian society. Just as America’s armed forces were on the vanguard of racial integration and later gender equality, perhaps they can lead the way on health care too. The Army Surgeon General established a Pain Management Task Force to look at alternatives to narcotics, and now the Army is using acupuncture and meditation to decrease narcotic use in the wounded. Sgt. Yates, the self-proclaimed “redneck hillbilly” who didn’t believe in Eastern Medicine, “decided to give it a shot,” and it worked.

I found the profile of Dr. Erin Martin the least hopeful in the near term. Initially shown as a primary care doctor in a low-fee clinic, Dr. Martin had high ideals, but was demoralized by too many patients and too little time. She was dissatisfied and frustrated by a system that made her job nearly impossible. Her escape fire was literally to escape: She quit the clinic, became a fellow in Dr. Andrew Weil’s Integrative Medicine program, and found a practice that supported her patient, humane approach. The film endorses this as the escape fire for primary care — but of course those clinic patients still need a doctor.

Dr. Martin’s path is similar to the one I took myself. Early in my career I worked for two years in a public mental health clinic. The patients were in great need, but the system was frustrating and the work demoralizing. Providing comprehensive, humane mental health care in such a system is an uphill battle at best, and in some respects nearly impossible. I have much admiration for those who work in such settings. However, like Dr. Martin, I chose to leave and practice in a way that makes more sense to me. While the makers of Escape Fire would likely endorse my choice, public mental health clinics still need doctors too. Moreover, it will be a long time before the American health care system rewards Dr. Martin and others who aim to avoid commodity care. Indeed, the system is accelerating in the opposite direction. Those of us who build this particular escape fire in essence work outside the larger system.

As I wrote at the outset, Escape Fire is a thoughtful indictment of the status quo. The film has been reviewed positively, and it strikes a nice balance between worrisome facts and emotional interest, ending on a hopeful note. We should have no illusions about easy solutions though. Healthier lifestyle choices are hard to pursue when fast food is cheap and tasty; a shift to preventative care from disease management would represent a fundamental sea change and a realignment of billions of health care dollars. For a start, at least, we can agree that American health care is burning, and that new solutions are desperately needed.

September 3rd, 2012  I’ll leave the “sloppy thinking” series for now, although I expect to return to it in the future. In this post I’ll share some thoughts about personal responsibility, especially as it pertains to the insanity defense. It’s a topic much in the news lately, due to tragic actions by now-household names such as James Eagan Holmes and Jared Loughner. The matter goes much further though. We normally assume that adults are responsible for their actions, and that these actions are freely chosen. The extent to which we treat this as absolute versus a matter of degree determines our fundamental political views, and how we view our neighbors and ourselves. I’ll leave the “sloppy thinking” series for now, although I expect to return to it in the future. In this post I’ll share some thoughts about personal responsibility, especially as it pertains to the insanity defense. It’s a topic much in the news lately, due to tragic actions by now-household names such as James Eagan Holmes and Jared Loughner. The matter goes much further though. We normally assume that adults are responsible for their actions, and that these actions are freely chosen. The extent to which we treat this as absolute versus a matter of degree determines our fundamental political views, and how we view our neighbors and ourselves.

Many facets of everyday life are premised on personal responsibility. The criminal justice system is the most obvious example. In a wider sense our willingness to live in community with others depends on each person taking responsibility for his or her behavior. Nonetheless, we’ve recognized exceptions to this default assumption for centuries. Adults who are severely sick or injured may temporarily be unable to assume responsibility for themselves. Likewise, infants and young children lack the ability to make informed choices and to exercise personal responsibility. Non-human animals are exempt from personal responsibility and are never considered guilty of a crime — well, not anymore.

English common law recognized that the same lack of responsibility extended to insane adults:

By the 18th century, the British courts had … developed what became known as the “wild beast” test: If a defendant was so bereft of sanity that he understood the ramifications of his behavior “no more than in an infant, a brute, or a wild beast,” he would not be held responsible for his crimes.

The history of the insanity defense then records the trial of Daniel M’Naughten in 1843, where inability to distinguish right from wrong was established as the crucial legal test. This became the standard, both in Britain and the US, for more than 100 years; the “M’Naughten rule” is still the legal standard in many states. Later modifications tended to liberalize its application, as with the “irresistible impulse” and “diminished capacity” doctrines, until the pendulum swung the other way in the wake of John Hinkley’s attempted assassination of President Reagan in 1981.

As a society, we seem to be losing our inclination to forgive the mentally ill, and children, when they commit horrific acts of violence. Even young teens are now tried as adults when an alleged crime is bad enough. And although insanity defenses are rare in U.S. courts, and their successful use often results in involuntary hospitalization longer than the prison sentence would otherwise have been, there is nonetheless a popular view that the insane “get away with it.” Jared Loughner recently plea-bargained for life imprisonment despite clear evidence of mental illness and the possibility of an insanity defense. The court will decide whether James Holmes has severe psychosis, an antisocial personality, or just a very bad attitude. As in Loughner’s case, this determination is unlikely to make a difference in terms of public safety — Holmes won’t be freed for decades, if ever. But the way we handle the question of legal insanity bears on how our society views itself.

Now that we are in a presidential campaign season, we hear rhetoric that cleaves the major parties around the question of personal responsibility. “You didn’t build that,” a slightly misspoken point by President Obama about the government’s role in promoting business, became a rallying cry for Republicans in defense of the entrepreneur. Yet both sides have a point: The government makes and maintains highways (and founded the internet); individuals create trucking companies (and online businesses). It’s really a matter of emphasis, and yet this emphasis is what most of the fighting is about.

Decades ago, social psychologists coined the term “fundamental attribution error” to highlight our tendency to over-apply dispositional or personality explanations to others, in the same circumstances we apply situational explanations to ourselves. E.g., if others are unemployed we often imagine they are lazy or unqualified (personal factors), whereas if we are unemployed, we often blame a tough economy and a lack of jobs (situational factors). Of course, some of the unemployed really are lazy or unqualified, just as some killers really have the criminal intent (mens rea) to be convicted of murder. The question is whether and to what extent we allow for exceptions in cases other than our own. Denying such exceptions flies in the face of our own legal tradition, our recognition of the fundamental attribution error, and our human kinship — the idea that we humans are more alike than we are different. We are wise enough not to punish infants or “wild beasts” even if they hurt us; the severity of their behavior and its consequences has no bearing on whether they are personally responsible. A person who cannot tell right from wrong due to severe psychosis is operating at the same level, and should be treated, not punished. Personal responsibility is a strong enough concept that it can withstand some nuance and flexibility — especially when that happens to reflect reality.

July 2nd, 2012  This fourth installment in my “sloppy thinking” series turns to psychotherapy, or what passes for it in some psychiatric practices. A very brief history: Sigmund Freud, a neurologist, invented psychoanalysis and its offshoot, psychodynamic psychotherapy, about 120 years ago. It was, first and foremost, a treatment that involved talking — not merely a conversation that happened to make the patient feel better. Years later, the object-relations school of psychoanalysis and the humanistic psychology movement of the 1960s partly shifted the focus of dynamic psychotherapy away from technique and toward a healing relationship, a shift prefigured by pastoral counseling and by the ministrations of the nursing profession. Nonetheless, dynamic psychotherapy remained a treatment: a professional service with clear goals and a coherent rationale, aimed to remedy defined psychological conflicts or deficits. Meanwhile, over the same century or so, academic psychologists developed the theories and practices of behaviorism via experiments with animals, and later applied behavior modification and various behavioral and cognitive therapies to human suffering. While such treatments could be offered in a humane and caring manner, the relationship itself was not considered curative. This fourth installment in my “sloppy thinking” series turns to psychotherapy, or what passes for it in some psychiatric practices. A very brief history: Sigmund Freud, a neurologist, invented psychoanalysis and its offshoot, psychodynamic psychotherapy, about 120 years ago. It was, first and foremost, a treatment that involved talking — not merely a conversation that happened to make the patient feel better. Years later, the object-relations school of psychoanalysis and the humanistic psychology movement of the 1960s partly shifted the focus of dynamic psychotherapy away from technique and toward a healing relationship, a shift prefigured by pastoral counseling and by the ministrations of the nursing profession. Nonetheless, dynamic psychotherapy remained a treatment: a professional service with clear goals and a coherent rationale, aimed to remedy defined psychological conflicts or deficits. Meanwhile, over the same century or so, academic psychologists developed the theories and practices of behaviorism via experiments with animals, and later applied behavior modification and various behavioral and cognitive therapies to human suffering. While such treatments could be offered in a humane and caring manner, the relationship itself was not considered curative.

Psychoanalysis and psychodynamic therapy originated in a medical context, and psychiatrists historically have been trained in its theory and practice. (In contrast, psychologists historically tended to practice the empirically based behavioral and cognitive therapies developed in academia, although this distinction between the disciplines has faded.) Prior to the advent of psychoanalysis, psychiatry was a medical specialty focused on the management of severe mental illnesses that rendered sufferers incapable of living in mainstream society. But by the mid-20th century, the field had adopted the new “talking cures” to treat higher functioning patients. For a few decades, roughly 1950 to 1980, the popular image of the psychiatrist was a psychoanalyst with the trademark couch in the office.

The emphasis in psychiatric training and practice shifted dramatically away from psychotherapy and toward medication treatments in the 1980s as a result of several factors. Promising classes of medications such as SSRI antidepressants and atypical neuroleptics were developed; federal research funding shifted toward biological psychiatry; psychiatry’s new diagnostic manual (DSM-III) encouraged medical-model thinking; managed care tightened the screws on reimbursement; and competition from non-physician mental health professionals heated up. Psychopharmacology became a defensible niche for psychiatry, unlike psychotherapy which saw increasing competition from psychologists, social workers, marital and family therapists, and others.

Currently, many American psychiatry residencies offer minimal training in psychodynamics, or psychotherapy in general (interesting debate here). I consider this very unfortunate. Psychodynamically informed treatment is far richer and more sensitive — ultimately, I have to believe, more effective — even if psychodynamic psychotherapy itself is not offered. For example, unconscious dynamics can help explain medication non-compliance, and can shed light on difficult psychiatric consultations on medical or surgical inpatients. It’s hard to deny that a mental health professional with a deeper appreciation of human emotions, conflicts, and psychological defenses has an advantage over the same professional without this appreciation.

Where’s the sloppy thinking? It results from the inescapable fact that most psychiatric patients harbor thoughts and/or feelings they want to talk about. A psychiatrist who avoids all such conversation feels like an “ape with a bone,” a medication technician who does his own little piece of work well, but misses the big picture. So the psychiatrist talks with the patient for 30, 45, or 50 minutes, which makes both the psychiatrist and patient feel better in the moment. It is billed as psychotherapy, but is it?

That depends on what happens in those 30, 45, or 50 minutes. Is it well-conducted cognitive-behavioral therapy? Hardly ever. Nor is it psychodynamic psychotherapy if it’s no more than a conversation that temporarily makes the patient feel better. Dynamic psychotherapy is a structured treatment that includes a dynamic case formulation, a coherent rationale, strategic interventions, and treatment goals — features uniformly absent in this typical scenario. Some call these unstructured conversations “supportive psychotherapy,” but even that has a technical definition and clear goals. Supportive psychotherapy is more than letting the patient “vent,” or chat as though it were a social visit. Perhaps all this mislabeling is an unfortunate mistake by well-meaning practitioners who were never trained to perform or recognize actual psychotherapy. Or maybe it’s intellectual laziness. Or insurance fraud.

An honest profession would call such encounters what they are: Humane medication visits. Stripped of the pretense of psychotherapy, we might admit that it often takes more than ten or 15 minutes to find out how a patient is doing, and that conversely it doesn’t require aimless (yet remunerated) chatting for the better part of an hour either. By clearly differentiating psychotherapy from generic doctor-patient conversation, we’d regain respect from other mental health professionals who have come to believe that psychiatrists don’t take psychotherapy seriously, or that we pompously claim we know what we’re doing when we don’t. These criticisms really boil down to irritation at psychiatry’s sloppy thinking about psychotherapy, a tragic irony considering the field’s long history with this treatment modality.

You guessed it: photo courtesy of Petr Kratochvil.

June 4th, 2012  This third installment in my series on sloppy thinking in psychiatry addresses something a little more subtle than “chemical imbalance” or polypharmacy. It is the growing vision, well represented by this recent editorial in Current Psychiatry, that the only salvation for the field lies in embracing the language and practice of neuroscience. With “chemical imbalance” discredited, attention has turned to functional brain imaging and genetics as our last and best hope to retain a shred of dignity as a medical specialty. Dr. Nasrallah’s editorial goes further than most, arguing that we need a new name for psychiatry: Psyche is an “archaic concept” that “has outlived its usefulness and needs to be shed.” Likewise, our “brilliant future anchored in cutting-edge neuroscience” will be hastened by renaming the major mental illnesses, calling psychotherapy “verbal neurotherapy,” and by embracing the language of “brain repair.” But it’s not all a matter of terminology: “The disastrously dysfunctional public mental health bureaucracy must be abandoned and transformed into ‘brain institutes,’ in all states, similar to cancer centers or cardiovascular institutes, where state-of-the-art clinical care, training, and research are integrated.” This third installment in my series on sloppy thinking in psychiatry addresses something a little more subtle than “chemical imbalance” or polypharmacy. It is the growing vision, well represented by this recent editorial in Current Psychiatry, that the only salvation for the field lies in embracing the language and practice of neuroscience. With “chemical imbalance” discredited, attention has turned to functional brain imaging and genetics as our last and best hope to retain a shred of dignity as a medical specialty. Dr. Nasrallah’s editorial goes further than most, arguing that we need a new name for psychiatry: Psyche is an “archaic concept” that “has outlived its usefulness and needs to be shed.” Likewise, our “brilliant future anchored in cutting-edge neuroscience” will be hastened by renaming the major mental illnesses, calling psychotherapy “verbal neurotherapy,” and by embracing the language of “brain repair.” But it’s not all a matter of terminology: “The disastrously dysfunctional public mental health bureaucracy must be abandoned and transformed into ‘brain institutes,’ in all states, similar to cancer centers or cardiovascular institutes, where state-of-the-art clinical care, training, and research are integrated.”

I share the sentiment, really I do. Wouldn’t it be great to see shiny Brain Institutes cropping up all over, replacing those sad, underfunded public mental health clinics? Wouldn’t we hold our heads higher if our business cards promised “verbal neurotherapy” and “brain repair”? We could call ourselves medical doctors without a hint of doubt or insecurity, sit proudly at the hospital cafeteria table with the other doctors — you know, the surgeons and cardiologists and such — and charge higher fees as a premier medical specialty instead of our current status as mental health “primary care.” There’s a lot to recommend this vision; where do I sign up?

Unfortunately, there is nowhere to sign up. This is a pipe dream. Psychiatry isn’t clinging to archaic language about the psyche out of nostalgia. It’s the best we have. “Verbal neurotherapy,” while technically a valid description of psychotherapy, is absurd hand-waving. By the same token, taking a vacation is “locational neurotherapy.” We aren’t going to gain anyone’s respect by dressing up our current practices in pseudoscientific jargon.

Nor are we withholding “behavioral neuroscience” from our patients now. In addition to the verbal neurotherapy, i.e., psychotherapy, that forms the mainstay of my practice, I also offer pharmaceutical neurotherapy, advice regarding nutritional and exercise neurotherapies, discussion of various occupational and relational neurotherapies — I even suggest an occasional locational neurotherapy. I simply lack the hubris, or perhaps it’s the marketing genius, to call it that.

When scientists develop safe, effective psychiatric treatments based on neuroplasticity and neuroprotection I’ll happily offer them to patients (or refer patients to centers where such treatments are available). When my Election Day ballot includes a measure to upgrade public mental health facilities to state-of-the-art Brain Institutes, you can count on my vote. I’m not holding my breath.

Kidding aside, there is nothing sloppy or ill-advised about incorporating neuroscience into psychiatry. Nor is it a new idea. From prehistoric trepanning to Freud’s 1895 “Project for a Scientific Psychology” (pdf of a 2004 review), from the introduction of neuroleptics in the 1950s (modern commentary here) to the “decade of the brain” in the 1990s, psychiatry has nearly always paid homage to the neural underpinnings of behavior. The only obvious exception was the heyday of psychoanalysis, from about 1950 to 1980. Otherwise, we use the best neuroscience we have at the time. The real problem, of course, is that we ask more of our neuroscience than it can deliver. Trepanning probably didn’t help, Freud abandoned his “project,” neuroleptics caused major side-effects and failed to allow patients to return to the community, and the “decade of the brain” turned many psychiatrists into drug-doling technicians. Science keeps improving, and I’m sure we’ll see good things emerge in the coming years. However, progress will occur at its own pace, and no amount of wishing or envisioning will make it happen any faster.

It is sloppy thinking to imagine that behavioral neuroscience is something new and revolutionary. The real revolution in psychiatry, if it ever happens, will be the integration of careful neuroscience, psychology, sociology, and other disciplines to elucidate and benefit our lived experience. This integration will incorporate, not supplant, our higher level understandings of psychology and psychodynamics. When psychiatry is ripe for the “creative destruction” of polarized thinking and choosing sides, it will be stronger than the sum of its parts, and will have finally reinvented itself into something we can unequivocally be proud of.

And yet again, photo courtesy of Petr Kratochvil.

|

|

A patient of mine recently observed that the increasing use of the the term “psychopath” in popular media is really a disguised way of criticizing selfishness. Dressing up selfishness as an odd and frightening clinical disorder — slapping a diagnostic label on it — makes for catchy news copy, and grants pundits emotional distance between themselves and those monsters who look just like us, but who lack the empathy and remorse that make us human.

A patient of mine recently observed that the increasing use of the the term “psychopath” in popular media is really a disguised way of criticizing selfishness. Dressing up selfishness as an odd and frightening clinical disorder — slapping a diagnostic label on it — makes for catchy news copy, and grants pundits emotional distance between themselves and those monsters who look just like us, but who lack the empathy and remorse that make us human.

I just read a mildly disturbing article in the New York Times called “

I just read a mildly disturbing article in the New York Times called “ The independent

The independent  I’ll leave the “sloppy thinking” series for now, although I expect to return to it in the future. In this post I’ll share some thoughts about personal responsibility, especially as it pertains to the insanity defense. It’s a topic much in the news lately, due to tragic actions by now-household names such as

I’ll leave the “sloppy thinking” series for now, although I expect to return to it in the future. In this post I’ll share some thoughts about personal responsibility, especially as it pertains to the insanity defense. It’s a topic much in the news lately, due to tragic actions by now-household names such as  This fourth installment in my “sloppy thinking” series turns to psychotherapy, or what passes for it in some psychiatric practices. A very brief history: Sigmund Freud, a neurologist, invented psychoanalysis and its offshoot, psychodynamic psychotherapy, about 120 years ago. It was, first and foremost, a treatment that involved talking — not merely a conversation that happened to make the patient feel better. Years later, the object-relations school of psychoanalysis and the humanistic psychology movement of the 1960s partly shifted the focus of dynamic psychotherapy away from technique and toward a healing relationship, a shift prefigured by pastoral counseling and by the ministrations of the nursing profession. Nonetheless, dynamic psychotherapy remained a treatment: a professional service with clear goals and a coherent rationale, aimed to remedy defined psychological conflicts or deficits. Meanwhile, over the same century or so, academic psychologists developed the theories and practices of behaviorism via experiments with animals, and later applied behavior modification and various behavioral and cognitive therapies to human suffering. While such treatments could be offered in a humane and caring manner, the relationship itself was not considered curative.

This fourth installment in my “sloppy thinking” series turns to psychotherapy, or what passes for it in some psychiatric practices. A very brief history: Sigmund Freud, a neurologist, invented psychoanalysis and its offshoot, psychodynamic psychotherapy, about 120 years ago. It was, first and foremost, a treatment that involved talking — not merely a conversation that happened to make the patient feel better. Years later, the object-relations school of psychoanalysis and the humanistic psychology movement of the 1960s partly shifted the focus of dynamic psychotherapy away from technique and toward a healing relationship, a shift prefigured by pastoral counseling and by the ministrations of the nursing profession. Nonetheless, dynamic psychotherapy remained a treatment: a professional service with clear goals and a coherent rationale, aimed to remedy defined psychological conflicts or deficits. Meanwhile, over the same century or so, academic psychologists developed the theories and practices of behaviorism via experiments with animals, and later applied behavior modification and various behavioral and cognitive therapies to human suffering. While such treatments could be offered in a humane and caring manner, the relationship itself was not considered curative. This third installment in my series on sloppy thinking in psychiatry addresses something a little more subtle than “chemical imbalance” or polypharmacy. It is the growing vision, well represented by this recent

This third installment in my series on sloppy thinking in psychiatry addresses something a little more subtle than “chemical imbalance” or polypharmacy. It is the growing vision, well represented by this recent