Even today there are patients who leave diagnosis and treatment entirely to their doctors. They make no effort to inform themselves about their illness or chart their own course; they do whatever their doctors advise. Once the norm, this passive, willfully naive attitude has withered in the face of a multigenerational attitude shift, coupled with the wealth of medical information at hand today. Direct-to-consumer drug ads on television, online peer support, medical websites and blogs of all stripes, “Dr. Google,” PubMed — it almost takes dedicated effort to avoid learning about one’s medical issue. The complementary role of doctors as kindly but authoritarian caretakers feels outdated by decades, and to many nowadays, offensive. “Paternalistic” has become the epithet of choice for doctors who fail to recognize, respect, and make room for patient autonomy and medical self-determination.

Even today there are patients who leave diagnosis and treatment entirely to their doctors. They make no effort to inform themselves about their illness or chart their own course; they do whatever their doctors advise. Once the norm, this passive, willfully naive attitude has withered in the face of a multigenerational attitude shift, coupled with the wealth of medical information at hand today. Direct-to-consumer drug ads on television, online peer support, medical websites and blogs of all stripes, “Dr. Google,” PubMed — it almost takes dedicated effort to avoid learning about one’s medical issue. The complementary role of doctors as kindly but authoritarian caretakers feels outdated by decades, and to many nowadays, offensive. “Paternalistic” has become the epithet of choice for doctors who fail to recognize, respect, and make room for patient autonomy and medical self-determination.

Most doctors practicing today, even those of us decades into our careers, began medical training at a time when patient empowerment had already gained ground in the U.S. Many of us supported it wholeheartedly. In college I studied medical ethics and patient autonomy. I volunteered at a community clinic called “Our Health Center” that aimed to empower patients. My stated goal when applying to medical school was to help patients take responsibility for their own health. Even today I tend to over-explain my reasoning to my patients, and to err — and sometimes it is an error — on the side of offering a smorgasbord of options along with their risks and benefits.

However, over the years the goalposts have moved. For a growing subset of patients it is no longer enough that we doctors talk to them as fellow adults. The one-time goal of shared decision-making has, in some circles, given way to a deep skepticism toward doctors and our expertise. Some regard us as irksome gatekeepers who add little to medical decision making and serve mainly as roadblocks to obtaining the medical tests or treatments they already know they need. In this jaundiced view, our role is reduced to rubber-stamping: ordering desired tests, signing requested prescriptions, drafting work excuses, and so forth. For example, I’ve received many calls from would-be patients seeking a prescription stimulant for self-diagnosed “adult ADHD.” The callers sound dismayed when I point out that my diagnosis may not agree with theirs. Similarly, patients seek me out to provide documentation and advocacy on behalf of a psychiatric disability they swear they have, but I haven’t yet evaluated. I find myself wishing that such callers could face the consequences of their own decisions without involving the unwanted, apparently superfluous impediment of a doctor.

These examples from my practice could be dismissed as drug-seeking or “gaming the system.” But skepticism toward physicians and our expertise goes much further. Patients insist on antibiotics for viral (or non-existent) infections. Parents refuse to vaccinate their kids. Online forums abound with horror stories of patients misdiagnosed and mistreated, who finally escape this nightmare only by taking matters into their own hands. “Ask your doctor” drug ads imply that doctors will fail to consider the advertised treatment if not for patient self-advocacy (and the generous assistance of a multimillion dollar marketing campaign). California has a voter initiative this fall that, among other provisions, would mandate random drug testing of physicians for the first time in the U.S.

There is a movement afoot to share medical records with primary-care patients, ostensibly for doctor-patient collaboration, but often justified on the basis of “transparency.” It is now deemed paternalistic for doctors to keep private notes of our own work, even though this is accepted in other professional and consultative fields. Institutions no longer trust us to do high-quality work without oversight by non-physicians who track quality and patient satisfaction measures. Some patients now balk when doctors ask personal questions, e.g., about religious practices or hobbies, that are not obviously related to a manifest disease process. Learning about our patients as people, their strengths as well as weaknesses, is apparently also paternalistic. Shouldn’t the patient decide what areas of information to divulge?

Reducing doctors to servile technicians renders us safely powerless. Never mind that we can no longer diagnose or treat illness as well, for example by drawing unanticipated connections between habits and disease. For many patients, and apparently for society at large, it is more important not to feel a power differential.

This is an odd sentiment indeed. Anyone offering a skilled service, professional or not, wields a degree of power — and at least a little paternalism — over clients or customers. The computer professionals and attorneys who come to my office expect their own clients to defer to their expertise. My mechanic knows more about cars than I do, my barber about hair, my grocer about what produce is in season. Somehow we don’t find it threatening to put our faith in these authorities, especially when they welcome dialog and involve us in the decisions and recommendations that affect us personally.

People sometimes wonder when they may question a doctor’s diagnosis or advice. I say always. I’ve spent a career encouraging patients to be curious, to ask questions, to understand their suffering and what may help. This is the legacy of patient empowerment: all of us taking responsibility for our own well-being, and medical professionals respecting the right of patients to make their own well-informed health care decisions.

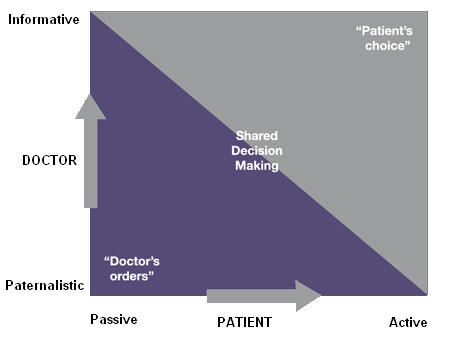

However — and it is a big however — this is not the same as physicians rubber-stamping everything patients believe or want. Shared decision-making lies between “doctor’s orders” and “patient’s choice” and follows the ethical standard of acting in the patient’s best interest (illustration courtesy of Practice Matters):

Nor should fear of sounding paternalistic silence us when detractors claim that everyone’s opinion is equally valid. It is falsely modest and politically naive to deny our own expertise. When it comes to medical matters, we doctors, while admittedly fallible, are nonetheless right far more often than we are wrong, and far more often than even intelligent, well-read non-physicians are. Like the attorney, computer professional, mechanic, barber, and grocer, we know things most other people do not. There is no shame in that, nor is it a power trip to point it out. A paternalism that demeans others is bad; a servility that demeans ourselves may be worse.

Top image courtesy of Ambro at FreeDigitalPhotos.net

Patients insist on antibiotics for viral (or non-existent) infections.

I know other people who are very concerned about antibiotic resistance and are appalled that their doctors offer them antibiotics, but they can’t find another doctor. Or a more subtle case: a friend who is a college professor in a small Texas town went to a doctor who supported her decision not to give her children too many antibiotics. The doctor said that that would make her individual child have stronger immunity to MRSA. My friend thought that this was bullshit and a misunderstanding of how antibiotic resistance develops. She talked to friends who were epidemiologists and virologists who confirmed her suspicions.

Another friend is a mathemetician at an R1 university. He’s perfectly willing to acknowledge that he’s arrogant and that this could get him in trouble if it were something serious, but he does have a better track record of diagnosing his minor to moderate ailments using google than many of the doctors he sees–certainly the ones he saw as a grad student.

And it just is true that a mathemetician with a Ph.D. from Princeton is smarter than the average doctor. Similarly, a statistician working at an academic medical center is probably able to evaluate evidence better than most doctors. The innumeracy of your average physician is really frightening. Most of my friends are pushing back against doctors who are prescribing the latest and greatest drug and bought into pharma advertising, not the other way around.

Similarly, a lot of ob-gyns are pretty obnoxious to young childless women who ask for IUDs even though the doctors are dead wrong on the evidence.

I also told a doctor in the ER that I was not going to fill the prescription he gave me for valium, because I knew that it would make me loopy. I also demanded zofran and specified orally-disintegrating tablets or IV after he gave me some percocet because of pain caused by a procedure he had done. His attending had botched it the first time, and he got to do it after observing it once.

I’ve been treated for bad nausea and know that I have a sensitive gag reflex. He was an anesthesiology resident with two weeks of experience in the ER. I wasn’t going to defer to his expertise.

Are you actually arguing that it’s doctors who push unneeded antibiotics, not patients who demand them? Because as a rule that’s absurd. You cite anecdotes about dull physicians set right by their smarter patients. Yes, I’m sure this happens. On the other hand, I can cite dozens of anecdotes about patients who misdiagnosed themselves, mismanaged their own meds, and so on. Every doctor in clinical practice can do this. Are you really arguing that non-physicians make better doctors than doctors?

A mathematician with a Princeton PhD is undoubtedly better at math than the average doctor — but could be far worse at medical decision-making, or English literature for that matter. “Smarter” isn’t the issue here. A biostatistician who can better evaluate medical evidence than most doctors would likely be unable to talk with a patient about her new cancer diagnosis. Cherry-pick a skill, and sure, there are other — rare, highly educated — people who can do it better than the average physician. Have a biostatistician review the research, a microbiologist identify the infection, a clinical psychologist counsel and support the patient, and so on. One physician integrates all these skills and many more.

Honestly, I wish it were legal for you to order your own Zofran (and IUD?) online. It’s a lose-lose proposition for contemptuous patients to see a doctor; both parties would be better off if it just didn’t happen. Unless the Zofran causes a fatal heart arrhythmia, of course.

I’m sorry. I should not have engaged. I was probably defensive, because your tone seemed condescending and arrogant.

I just think it’s silly to argue that most patients most of the time are provided with the standard of care in the U.S. There’s ample evidence that this is not the case. For example, too many diabetics do not get referred for regular eye screenings. And many people are prescribed medications that they should not, e.g., there are very high rates of prescriptions of antipsychotics among children in foster care. Very few of these are probably justified; physicians have not done a great job of policing themselves, and under those circumstances it’s hard to listen to arguments from the members of a guild.

I’m also probably defensive. In my experience, the best doctors are exceedingly modest about their abilities and very honest about the limits of their knowledge. I think I’m calling for a little bit of epistemic humility.

I’m sorry. I should not have engaged. I was probably defensive, because your tone seemed condescending and arrogant.

My thoughts exactly.

I just think it’s silly to argue that most patients most of the time are provided with the standard of care in the U.S.

They are, by definition. That’s what “standard of care” means. But I agree that the status quo is far from ideal. Frankly, I’ve been critiquing the ills of medicine for decades. That’s why I get defensive when I’m considered an arrogant “member of the guild” by someone who seems more than willing to throw the baby out with the bathwater. If you truly don’t see value in doctors (or Western medicine, etc), please make yourself and us happier by going elsewhere. Meanwhile, tens of thousands of doctors will be repairing heart valves, helping people breathe, removing cancers, decreasing stroke risk, helping hallucinated voices go away, and relieving itchy rashes. My post was exactly about humility — on both sides of the doctor-patient relationship.

15 minute med-checks in psychiatry pass for the standard of care because they are what happen. So, in a legal sense you’re right. 15-minute med checks are not the standard of care recommended by research. (I know quite well that you don’t support 15-minute med checks.) By standard of care I meant “recommended by research criteria”.

“If you truly don’t see value in doctors (or Western medicine, etc.)”

I’m going to walk away now, but I will only say that you may have caught me on a bad day, and you certainly don’t know me. I don’t think that I wrote anything which could be construed as being against Western medicine. Nothing, for example, makes me angrier than people who refuse to vaccinate their children for woo reasons.

Dr. Reidbord,

You make some good points. I am sure my PCP recently thought I was one of those patients although I didn’t demand any drugs. 🙂 I thought I was communicating one thing and I think she thought she heard something else. Unfortunately, I didn’t realize this was a problem until speaking to her on the phone about the situation. I am wondering if it would be a good habit to get into of summarizing the situation at the end of the appointment to make sure we are both on the same page in the future.

Regarding antibiotics, this is probably beyond the scope of this blog entry but I would love to see a discussion about whether the routine prescribing of these drugs postoperatively for various operations is supported by research. When I was considering having surgery, it didn’t seem to be but I only briefly pursued it with the surgeon and was too scared to push too hard.:)

I admit I have gone to the doctor before for a virus that lingered not because I wanted a drug, but because I wasn’t sure it was a virus. The physician assumed that I wanted an antibiotic and in fact offered me one. I didn’t want an antibiotic if one wasn’t needed, I wanted the physician’s opinion. I’m perfectly fine (and happy) to leave without a script. When she offered me an antibiotic, I asked if I needed it. She said, probably not. So, I think it does go both ways. Patients shouldn’t go in requesting medications, and physicians shouldn’t assume that if the patient showed up it means they want a medication.

My first visit with my internist also resulted in some faulty assumptions. I went for a physical because I hadn’t had one in several years. The first thing the internist said to me is, “I can’t refill the Vyvanse, but I can refill the other drug.” I was a little irritated because I wasn’t there for a drug refill. The ironic thing is I argued with the psychiatrist about putting me on Vyvanse, because I was afraid other doctors might look at me as a drug seeker. And, that turned out to be the case. I let him know I wasn’t there for a drug refill and my psychiatrist handled that thank you very much. We worked it out, and he’s been a good doctor.

On the other hand, I had a good experience with my psychiatrist when I wanted to ask him a question about some research but was concerned he might see it as me questioning his treatment decisions or tying to be a know it all. I wanted to ask him about the research showing brain volume loss with antipsychotics, and he was very nice and receptive to my questions. I appreciated his response, because I wanted to know his opinion and didn’t want to be offensive. I know sometimes it’s touchy when a patient brings up research they’ve read. I’m glad he didn’t take it wrong.

I go to the doctor when I don’t know what to do. I don’t want physicians to assume I showed up to get drugs.

Most likely a problem of communication? A bit like this thread.

Plus, there is the nasty interference of third-parties making medical decisions. Although why most people take it out on physicians instead of insurance companies or government, astounds me. I find it almost comical the way many people let themselves be pushed around by government or their employers, but think they have the right to expect their doctors to do what they say.

Not the way I roll, yet I don’t know if you would still be offended by my approach or not. I will say it is no different than how I approach any other professional. Actually, I’ve gotten more second opinions for car problems and law issues than I have with any medical issues.

I consult physicians as expert resources; nothing more, nothing less. And, I value their experience more than their training. However, I have been finding over the years that my physician’s thinking has become more limited not less. Whether due to the current one-size-fits all approach to medicine, the mandates of insurance and .gov, no time to speak with patients or just too many patients who have “burned them”, I don’t know.

BTW, I always get copies of my medical records when I can. I have done so since I worked in a hospital and could print many of them at my workstation. Back in those days, you had to get sign off from your physician before you could even look at them. Yet, I was never denied access. There isn’t anything nefarious in my asking for copies. I save them in case I need to reference them in the future, and having them has been very helpful to me over the years.

I don’t claim to know more than my doctor but I know my body. I have been to A LOT of doctors good ones and bad ones, and right now I have some really good ones. In the past I have been to some that just do not listen. I am 27 and started having “behavioral Problems” around age 10. The doctors listened to my mother more than me and in my opinion that was a mistake. I received countless diagnoses and medications as a result. I also endured some nasty side effects because they wren’t listening to me. I eventually did get what I feel is the right diagnosis. I think situations this leads people to lack trust in their doctors. So it is up to the patient to be educated, but doctors need to be listening so they render an accurate diagnosis and prescribe an effective treatment. Patients also need to understand that medicine is not an exact science, and sometimes mistakes will happen, which is why they need to be educated and have an open line of communication with they doctors. Great post Doctor!