A few years ago I wrote that uncertainty is inevitable in psychiatry. We literally don’t know the pathogenesis of any psychiatric disorder. Historically, when the etiology of abnormal behavior became known, the disease was no longer considered psychiatric. Thus, neurosyphilis and myxedema went to internal medicine; seizures, multiple sclerosis, Parkinson’s, and many other formerly psychiatric conditions went to neurology; brain tumors and hemorrhages went to neurosurgery; and so forth. This leaves psychiatry with the remainder: all the behavioral conditions of unknown etiology. Looking to the future, my fervent hope that researchers will soon discover causes and definitive cures for schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and other psychiatric disorders comes with the expectation that these conditions will then leave psychiatry for other specialties. We will always deal with what is left. At minimum we psychiatrists should accept this reality about our chosen field. After all, there appears to be no alternative. Some of us go beyond this to embrace uncertainty as intellectually attractive. We like that the field is unsettled, in flux, alive.

A few years ago I wrote that uncertainty is inevitable in psychiatry. We literally don’t know the pathogenesis of any psychiatric disorder. Historically, when the etiology of abnormal behavior became known, the disease was no longer considered psychiatric. Thus, neurosyphilis and myxedema went to internal medicine; seizures, multiple sclerosis, Parkinson’s, and many other formerly psychiatric conditions went to neurology; brain tumors and hemorrhages went to neurosurgery; and so forth. This leaves psychiatry with the remainder: all the behavioral conditions of unknown etiology. Looking to the future, my fervent hope that researchers will soon discover causes and definitive cures for schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and other psychiatric disorders comes with the expectation that these conditions will then leave psychiatry for other specialties. We will always deal with what is left. At minimum we psychiatrists should accept this reality about our chosen field. After all, there appears to be no alternative. Some of us go beyond this to embrace uncertainty as intellectually attractive. We like that the field is unsettled, in flux, alive.

Yet many of us clutch at illusory certainty. Decades ago, psychoanalysis purportedly held the keys to unlock the mysteries of the mind. It later lost favor when many conditions, particularly the most severe, were unaffected by this lengthy, expensive treatment. Now the buzzword is that psychiatric disorders are “neurobiological.” This is said in a tone that implies we know more than we do, that we understand psychiatric etiology. It’s a bluff.

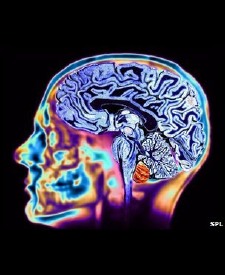

Patients are told they suffer a “chemical imbalance” in the brain, when none has ever been shown. Rapid advances in brain imaging and genetics have yielded an avalanche of findings that may well bring us closer to understanding the causes of mental disorders. But they haven’t done so yet — a sad fact obscured by popular and professional rhetoric. In particular, functional brain imaging (e.g., fMRI) fascinates brain scientists and the public alike. We can now see, in dramatic three-dimensional colorful computer graphics, how different regions of the living brain “light up,” that is, vary in metabolic activity. Population studies reveal systematic differences in patients with specific psychiatric disorders as compared to normals. Don’t such images prove that psychiatric disorders are neurobiological brain diseases?

Not quite. Readers of these exciting reports often overlook two crucial facts. First, these metabolic differences only appear in group studies and cannot be used to diagnose individual patients. As of this writing there is no lab test or brain scan to diagnose any psychiatric disorder. Attempting to do so would be like diagnosing malnutrition based on height. While malnourished people are shorter than the well-nourished on average, there is wide overlap and height is not diagnostic. Second, etiology — the cause of these differences in brain function — remains unknown. Differences in brain function (and structure) are not necessarily inborn. Brain anatomy can change as a result of life experience, and metabolic activity (function) from experimental manipulation of cognitive effort, induced mood, guided imagery, etc. Just as multiple factors affect a subject’s height, multiple biological and psychological factors affect brain findings as well. Thus, learning that patients with borderline personality show decreased metabolism in the frontal lobes (hypofrontality) is neither surprising nor indicative of a neurobiological etiology. We already know the frontal lobes inhibit impulsive activity, and we already know borderline personality is characterized by impulsivity. What else would we expect?

Genetic studies consistently show both heritable and environmental factors at play in psychiatric disorders. Since the 1960s, psychiatry has called this combination the diathesis-stress model: an inborn predisposition meets an environmental stress, leading to an overt disorder. The model helped shift the field from “nature versus nurture” to “nature and nurture” — and no research discovery or neurobiological rhetoric so far has shifted it back. Patients and their doctors still contend with diathesis and stress: recreational drug use tips one patient into psychosis, sudden abandonment tips another into borderline rage. Indeed, clinicians remain much more able to influence stress than diathesis. A dispassionate assessment of what we currently know should lead to humble agnosticism about psychiatric etiology. Genetics, biology, and environment all play a role, but beyond that there isn’t much we can say. This is why all current psychiatric medications treat symptoms and are not curative.

In this light, the popularity and zeal of neurobiological language is startling. The American Psychiatric Association (APA) subtly changed the wording in its new Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, DSM-5, to imply that all psychiatric conditions are biological in nature. The National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) assumes that “Mental disorders are biological disorders….” The National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI) says, “A mental illness is a medical condition….”

A more ground-level version is expressed by editor-in-chief Henry A. Nasrallah, MD in the latest edition of Current Psychiatry. In an editorial not-so-subtly titled, “Borderline personality disorder is a heritable brain disease,” Dr. Nasrallah proclaims BPD a “neurobiological illness” and “a serious, disabling brain disorder, not simply an aberration of personality” — as though these were distinct alternatives rather than two terms for the same thing. After citing a number of biological findings which fail to prove etiology (e.g., the hypofrontality mentioned above) and which show partial heritability, Dr. Nasrallah concludes that “the neuropsychiatric basis of BPD must guide treatment.”

Of course, it already does. We already treat borderline personality disorder the best we know how, with psychotherapy (shown by functional imaging to modify brain metabolism, by the way) and often with adjunctive medication to treat symptoms. What more do breathless declarations of brain disease buy us, other than reduced credibility? It’s not as though any of us currently withhold neurobiological treatment as a result of outmoded ideology. On the contrary, the moment the FDA approves a cure for borderline personality disorder based on an established neurobiological etiology, I will gladly refer my patients to the neurologist, virologist, or genetic counselor who would thereafter treat such patients.

I hope that when Dr. Nasrallah says “the neuropsychiatric basis of BPD must guide treatment,” he’s not referring things like using ECT when meds fail to help the chronic depression of BPD patients.

I’ve seen that approach firsthand, and it was one of the things that clarified for me more than anything else the fallacies of the neurobiological approach.

Steven,

I admire your rhetoric but “breathless declarations” at least of neurobiology get us focused on the organ of interest. Kandel takes a much more measured approach in his recent book when he advocates that while you can’t localize “love” in the brain anymore that you can probably localize any other behaviors that represented in networks of neurons – it never the less makes perfect sense to study the condition of love using the reductionist techniques of neuroscience.

The polemics about neurobiology or brain disease are the modern day equivalent of the argument of medications versus psychotherapy in the early days of biological psychiatry.

The sooner we drop the new polemic like we did the old one – the better. Either extreme is a fallacy. I framed it this way for a conference where I am presenting on the neurobiology of addiction:

http://gdpsychtech.blogspot.com/2014/04/framing-presentation-on-neurobiology-of.html

I think the neurobiological changes are dynamic rather than static. To use Kandel’s 1979 example, if I talk with my therapist for several hours and that results in plastic or experience related changes in my brain – is that a neurobiological change or is it the magic of psychotherapy?

GD

Hi George,

Who is the “us” who needs to focus on the organ of interest? I completely support brain research in psychiatry, and also in psychology. It makes perfect sense to me to study subjective states such as love using neuroscience. As a matter of fact, 20+ years ago I published a couple of studies on psychophysiology collected during psychotherapy sessions, looking for hard-data correlates of subjective states.

However, research isn’t clinical practice. Nowadays I focus on the organ of interest by conducting psychotherapy and prescribing meds for symptomatic relief (and prophylaxis). The polemics about neurobiology aren’t aimed at researchers, they’re misdirected at clinicians and the public. I’d prefer to let the research community do its work, while the rest of us are spared the overheated pronouncements and premature conclusions.

Kandel’s 1979 example: Both, of course.

The “us” here is psychiatry.

Many of us are more involved in brain function than others. As an example, for 23 years I ran an inpatient unit and Geriatric Psychiatry and Memory Disorder Clinic. Like any other doc I looked at all of the CT and MRI scans that I ordered and discussed the results with a neuroradiologist. I also taught the stuff to med students and residents. I also did the PRITE review on neurology for years.

The idea that psychiatrists learn something about the brain in residency and then forget about it seems like old school to me. Leaving neuroscience up to the neuroscientists is a quick way to become obsolete, but I suppose there are plenty of people with the viewpoint that psychiatry is an obsolete speciality. I am of the opinion that psychiatrists need to know about brain functioning ranging from overt brain disease to the substrates and theory involved in generating a normal conscious state. Some of that research is being done right now in psychiatry departments by psychiatrists.

From a professional standpoint, I think there needs to be more awareness of basic neuroscience and its importance by practitioners. When people tell me they prefer reading a text by Stahl (I don’t) – I don’t know if that means they put it under their pillow at night or they actually understand it.

So that knowledge is currently needed for both technical expertise and teaching purposes. The bodies responsible for professionalism should make it explicit – but they are known for their guess what I am thinking agenda. Some of that is always neuroscience.

GD

1: Tononi G, Koch C. The neural correlates of consciousness: an update. Ann N Y

Acad Sci. 2008 Mar;1124:239-61. doi: 10.1196/annals.1440.004. Review. Erratum in:

Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2011 Apr;1225:200. PubMed PMID: 18400934.

Yes, psychiatrists should know about the brain, and practitioners should be aware of basic neuroscience and its importance. As I see it, this has exactly nothing to do with polemics (your word) or overblown rhetoric (mine) that psychiatric conditions are “neurobiological.” This is a political assertion, not a scientific one. As your Kandel quotation conveys so well, it’s absurd to pit neurobiological change against psychosocial effects, as though we were rooting for opposing teams, or having an argument over communism versus capitalism. It’s all neurobiology… and psychology… and genetics… and environment… and so on. Psychiatry has a wide purview, from the cell to society. One faction screaming that they’re the “most fundamental” is just annoying and embarrassing.

I keep hearing about studies which show those with schizophrenia do better in developing countries than in the U.S. I don’t know enough about these studies to have an opinion, but I am curious about your thoughts. Are they finding that they have better family support, social inclusion, more persons with mental illness working rather than on disability, etc?

Thanks

I was delighted to read your May 1 2014 blog post, “ Dealing with the Behavioral Conditions of Unknown Etiology “ where you state, “Some of us go beyond this to embrace uncertainty as intellectually attractive. We like that the field is unsettled, in flux, alive. I’m reminded of your January 27, 2011 blog post, “Embracing Psychiatric Uncertainty,” where you state, “Frankly, this very uncertainty — mystery, if you will — is one of the things I like about psychiatry. It isn’t a settled area. It is endlessly debatable, much like an undergraduate philosophy course.”

According to several researchers, psychiatrists, along with family physicians, are supposed to ‘tolerate’ clinical uncertainty better than other medical specialties. This phrase is used repeatedly by a variety of researchers (references are available upon request!), but my colleagues and I, at least as regards, primary care physicians, are wondering why should it be mere ‘toleration?’ Given that tackling undifferentiated, ambiguous problems is why so many patients go to see a primary care physician in the first place, why shouldn’t PCPS make themselves into the experts for dealing with clinical uncertainty? One good reason at least –it’s often a long, hard slog!

In our new book, “Clinical Uncertainty in Primary Care: The challenge of collaborative engagement,” my colleagues and I suggest that the pervasive uncertainty that PCPs live with daily might be better managed through facing it together (i.e., collaborative engagement), and the book both digs deeply into the meaning of uncertainty in primary care medicine as well as ways it might be engaged through collegial collaboration. And here’s my question for you: I’ve been told over the years by my numerous friends in psychiatry and psychology that for PCPs to do this well, they need to take a page from the psychiatrists who, at least the good ones, routinely engage in supervision – a process where dilemma cases – cases for which they are stuck for whatever reason – are presented for discussion to at least another psychiatrist if not a small group. (Many of the small group methods described in the book come, in part, from several authors’ experience with ‘supervision,’ the Balint group method, for example). Is this your understanding as well? How do you think this works in actuality to help deal with clinical uncertainty in psychiatric practice? Please give me your experience with supervision for dealing with clinical uncertainty in psychiatry and correct what might be some misperceptions!

Lucia Sommers

PS Our book can be accessed for free if your medical library has the Springer platform. Once connected to your library, put: http://www.springer.com/medicine/book/978-1-4614-6811-0 into the browser and follow the prompts to free download.

Thank you very much for your comment and your kind words. Instead of replying here, I wrote a blog post with more thoughts about how to enjoy (not just tolerate) clinical uncertainty. I welcome your further thoughts and comments.

Hi Steve,

Not sure if you would want to post this (or how you’d do it) but I did want you to know that I referenced your blogpost on uncertainty in my response on Mike Cadogan’s blog “Life in the Fastlane”. (See below.) Mike is a very thoughtful Australian ER doc. As you will see from reading other folks’ responses to his post,“The emotional strain of healthcare’, the need for clinician support for being a caregiver is huge.

I encourage you to keep writing about these issues!

Lucia Sommers

[text of Mike Cadogan’s blogpost and Lucia Sommers’ commentary deleted, I added links to them above — SR]

Lucia,

Thank you again for your kind words and encouragement. As luck would have it, my post on enjoying clinical uncertainty was picked up by KevinMD.com, where it will appear tomorrow (5/16/14). You may wish to comment on it there, before a wider audience. Best wishes.

I could help but read with much attentions to the observations and assertions you made most based on known research study and history. Much of what you said I suspected quite a bit. I couldn’t help saying to myself “I th0ught so” which I repeated more than once.

No doubt in my mind that clinicians are given way too much credit to the chemical imbalance of the brain. Am now hearing about brain disease of addictions. We just do not know enough about the brain yet to maker such assertions with so much force and confidence.

Please do not make yourself obsolete. You thinking is too clear and it will be missed. I would prefer if you continue to reflect on the available research knowledge and help us refine our theories so that we can serve people better.

http://theworsetreatmentever.blogspot.com/

I would truly be humiliated to be part of the medical field today. The job of a physician is to diagnose disease and treat appropriately. There are so many medical conditions causing depression and anxiety and doctors are so poorly educated in the US that they treat these conditions with a drugs vs even attempting to diagnosing the disease further destoying the lives of human beings. Yet if you are a narcissist which has been acquired due to your situation as a physcian in the US, then you only treat humans as objects and you truly don’t care about all the lives you destroy. Check out http://www.parathyroid.com to educate yourself about a disease that destroys millions of peoples lives which is easily curable in 5 minutes with a skilled surgeon. It’s more common then you were ever taught. Just do the research. Also Cluster B personality disorders which some are morally insane are not treatable and unfortunately part of the reason the US has fallen apart. Many white collar professionals in the US have this condition which makes it scary to go to any of these professions. In the 70’s we called the behavior of white collar professionals today “white trash”. Welcome to the United States of Psychopaths!

I almost didn’t post your comment, as it seems to combine a wild rant with an ad for the linked parathyroid surgery center. The truth is, physicians treat many conditions that are not diagnosed diseases. We treat syndromes like fibromyalgia and chronic fatigue, and isolated symptoms like headache, dry eyes, and lower back strain. And even when we do diagnose a disease, we often don’t know what caused it, e.g., essential hypertension. If this uncertainty would humiliate you, then it’s a good thing you’re not part of the medical field today.

Many medical conditions can cause depression and/or anxiety — including parathyroid tumors, although they’re not particularly high on the list. Would you favor brain MRIs for all depressed patients, to make sure they don’t have a tumor? Without other symptoms to suggest a brain tumor, this expensive test will be useless over 99% of the time. We could also do spinal taps on all depressed patients, to make sure they don’t have a hidden tuberculosis infection in the brain. The reason we don’t is that the cost in money, medical risks, and discomfort outweigh the expected benefits. But it is a good idea to have a general medical checkup and some basic lab work to check for common medical causes of depression and anxiety, e.g., anemia, diabetes, thyroid disorders. It’s a matter of medical debate where to draw the line.

Narcissism isn’t “acquired” by being a physician, although it’s possible that people who are already narcissists gravitate to the field. This is a good research question, but not a very savvy putdown. Narcissists also likely gravitate to other professional fields — and even to blogging and commenting on blogs. “Moral insanity” is an outmoded term from the 19th century. Cluster B personality disorders are difficult but possible to treat with psychotherapy. Some white collar professionals in the US (and elsewhere) have these conditions, as do blue collar and unemployed people. Here’s a HuffPo article about psychopaths.