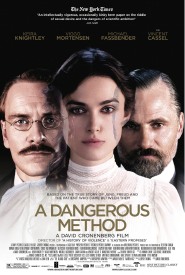

Tonight I was invited to an advance screening of “A Dangerous Method,” a film about the early days of psychoanalysis. It stars Keira Knightley, Michael Fassbender, and Viggo Mortensen, and will be in wide release by Sony Pictures Classics this month. The invitation was extended to Psychology Today bloggers, among others, in the hope we’ll publicize the release. Since I was gifted with a free viewing, I invite readers to consider this review with my potential conflict of interest in mind.

Tonight I was invited to an advance screening of “A Dangerous Method,” a film about the early days of psychoanalysis. It stars Keira Knightley, Michael Fassbender, and Viggo Mortensen, and will be in wide release by Sony Pictures Classics this month. The invitation was extended to Psychology Today bloggers, among others, in the hope we’ll publicize the release. Since I was gifted with a free viewing, I invite readers to consider this review with my potential conflict of interest in mind.

Overall, I was pleasantly surprised by the film, which has received mixed but mostly positive reviews so far. It humanizes both Freud and Jung, and introduces us to Sabina Spielrein, a real-life patient of Jung who later became a renowned psychoanalyst herself. Jung’s reputed sexual affair with Spielrein is treated as fact in the movie, and serves as the main dramatic focus. Some reviewers feel Knightley overacted the part of Spielrein. I thought it was pitched about right: a troubled young woman having illicit sex with her therapist would naturally be agitated and volatile. I did find Spielrein’s willingness, from the first session, to participate in newfangled psychoanalysis to be a bit optimistic. Also, her suggestion at one point that “there is man in every woman, and woman in every man” too-neatly implies that she gave Jung his idea of the anima and animus. Nonetheless, Spielrein is very well played.

In contrast, I found Fassbender’s portrayal of Jung more vague and wooden. The film suggests he was a psychic who could foretell the future in dreams and premonitions. His feelings toward Spielrein seem confused, not merely ambivalent or conflicted. And he refers to countertransference years before Freud published the term, although it could be argued the two historical figures may have discussed it between themselves earlier.

The decline and fall of Freud and Jung’s collaboration is the secondary theme, and here I was particularly impressed with the believable way Freud was portrayed. A pioneer, pragmatist, and controlling intellectual, he knew his treatment approach was controversial and sought to rein in Jung’s more expansive and spiritual predilections, which the elder Freud saw as giving ammunition to his enemies. Instead of the usual stereotype as a gruff, unyielding father figure preoccupied with sex, Mortensen plays Freud as somewhat authoritarian, but fundamentally smart, affable, and very concerned about the future of his psychoanalytic movement. Their famous 1909 falling-out on the deck of a ship sailing to America is played with a soft touch: Freud refuses to let Jung analyze his dream for fear of losing his authority (something Jung later recounted as due to Freud’s secrecy over his affair with his sister-in-law Minna Bernays). In the film, Jung is hurt by this non-reciprocity, and goes on afterward to develop his own theories of the psyche.

The film is beautifully photographed, and has a number of nice touches. The opening and closing credits are shown over a close-up of handwritten correspondence, the main way Freud and Jung communicated with each other. In one scene Jung conducts a word-association test using physiologic data collection — an accurate depiction of some of his research at Burghölzli, the psychiatric clinic of Zurich University, where he worked from 1900–1908. I even liked how the film showed the evolution from horse drawn carriages to automobiles, which of course happened in the same time period.

The American physician-psychologist William James was Freud’s contemporary and wrote: “I can make nothing in my own case of his dream theories, and obviously ‘symbolism’ is a most dangerous method.” The film “A Dangerous Method” is not nearly so dismissive of psychoanalysis. Yet, in its depiction of the dueling dream interpretations of Freud and Jung, and the complex relationship between Jung and Spielrein, it deftly highlights how symbolism is indeed a dangerous method of transacting human relationships.

Leave a Reply