In my last post, I outlined the fundamental problem facing advocates of nonviolence: Despite nearly universal conceptual agreement with this goal, human psychology conspires to make peace elusive and strife apparently unavoidable. Our emotions trump our rationality, biasing assessments of real-world evidence and leading to post-hoc justification of whatever our “gut” feels. Unfortunately, and rightly or wrongly, our gut feels scared or mistreated much of the time. Violence is often the result, whether construed as self-defense or justified retribution. This occurs with individuals, groups, and nations, and behaviorally ranges from brief verbal expressions of contempt to weapons of mass destruction and genocide.

In my last post, I outlined the fundamental problem facing advocates of nonviolence: Despite nearly universal conceptual agreement with this goal, human psychology conspires to make peace elusive and strife apparently unavoidable. Our emotions trump our rationality, biasing assessments of real-world evidence and leading to post-hoc justification of whatever our “gut” feels. Unfortunately, and rightly or wrongly, our gut feels scared or mistreated much of the time. Violence is often the result, whether construed as self-defense or justified retribution. This occurs with individuals, groups, and nations, and behaviorally ranges from brief verbal expressions of contempt to weapons of mass destruction and genocide.

Gut reactions cannot be overcome by rational argument alone. “Fight or flight” responses to threat, and urges to inflict retribution or punishment, start at the emotional level. Since it is unrealistic to hope for a world without emotional triggers — without perceived threats that “demand” violent self-defense, or injustice that “demands” violent retribution — those who advocate nonviolence must accept the reality of emotional provocation. Another reality is that even those who endorse a nonviolent philosophy are saddled with the same emotional reactivity as everyone else. Given these constraints, how can nonviolence be promoted an emotional level?

Safety

It has often been said that our physiologic response to stress serves us well in situations for which it was originally designed, e.g., an attack by a wild animal, but that it is misplaced in our modern world of “attacks” by time deadlines, career pressures, and miscommunication by loved ones. Autonomic stress responses — increased pulse and blood pressure, outpouring of stress hormones, faster reaction time — may save our lives in dire situations, but only hurt and exhaust us when activated chronically and without purpose. Many effective ways of managing unhealthy stress do so by enhancing feelings of safety and relaxation, emotions that are incompatible with the stress response.

In many respects, violence is similar. With rare exceptions, it is a reaction to a perceived threat. It may be said that violence serves us in situations “for which it was originally designed”: self-defense against a warring enemy or a criminal intent on killing us. Yet it only hurts and exhausts us individually and as a species when activated chronically. Enhancing feelings of safety and relaxation helps us be less violent and more peaceful; conversely, a heightened sense of danger and tension promotes violence. While dangerous threats exist in the real world, they trigger violence emotionally, not rationally. Being cut off in traffic may constitute a real physical threat, but our urge to respond with verbal or physical violence arises from a complex stew of imagined contempt by the other, anonymity in our vehicle, an assessment of the likelihood of further escalation, how much we feel they “deserve” it, and similar factors. Emotional safety is complex and not easily assured. Yet it is a necessary element in our closest relationships, in our work, in our communities, and on the world stage. When it is lacking, violence often results.

Humanization of the Other

This is perhaps better stated in the negative: It takes dehumanization to commit violence. From schoolyard putdowns to racial epithets to “the enemy” in wartime, our thoughts and language serve to make emotionally driven violence acceptable. It is hard to treat another person as expendable or deserving to suffer while imagining his or her grieving parents or children — so we take pains not to. Seeing each other as cherished, capable of suffering, and harboring a unique view of the world — in a word, human — is another necessary element for promoting nonviolence. Without it, people are means to an end, not ends in themselves.

Role Models

Depicted with the prior post was Mahatma Gandhi, the first to apply nonviolent principles to politics on a large scale. Gandhi’s nonviolent philosophy, which he termed satyagraha, would likely have had little influence without his personal actions and role-modeling that led to political change in India and elsewhere. Gandhi modeled nonviolence working. Role models such as Gandhi, Martin Luther King, Jr., and Jesus of Nazareth show others a peaceful path by modeling not only behavior, but also emotion: the courage to act according to ideals, without succumbing to fear that might otherwise justify violence.

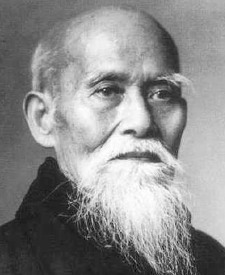

A similar role model is depicted with this post. Morihei Ueshiba (often called O Sensei, or Great Teacher) founded the Japanese martial art of aikido. Based on earlier violent styles, aikido aims to neutralize violent attack while leaving the attacker unharmed. Aikido’s core principle of harmonizing one’s physical and spiritual energy with the attacker’s would be little more than esoteric philosophy if not for its practical application. As Gandhi did in politics, Ueshiba modeled nonviolence working, in this case against literal physical attack, and in a manner that can be learned and practiced by others.

Early Learning

Patterns of emotional reactivity are established in early childhood. While a propensity to violence may be inborn, nonviolent alternatives can be introduced quite early as well. A society dedicated to nonviolence would teach this in preschool, introducing more sophisticated and challenging scenarios in grade school and beyond. Such a curriculum would not pretend that the world is a peaceful place. Maintaining a nonviolent stance in a world that seems to demand the opposite is a lifelong challenge. All the more reason to start confronting this challenge as soon as possible, ideally before personality is codified and harder to influence.

Practice

It’s one thing to aspire to an ideal, quite another to behave accordingly. There is no substitute for practice, “walking the walk” as well as “talking the talk.” Emotion may trump rationality, but intentional action (and well-chosen cognitions) can shape emotion. Practicing peaceful conflict resolution may occur in daily life, of course. But in addition, dedicated training or exercises may be necessary elements. For example, disciplined participation in nonviolent political action, or in aikido training, may instill peaceful “reflexes” in a way that merely hearing or reading about these practices cannot.

In this post I outlined ways of promoting nonviolence, taking into account emotional and worldly realities. This list is very general and far from exhaustive, and is offered in the spirit of collaboration and discussion. Instead of dividing ourselves by tactics — more guns laws or fewer? death penalty or not? — common ground seems a better place to start. Most of us seek peace, yet most of us share emotions that feed violence. This makes a peaceful world an elusive yet worthy goal we can work toward together.

Hi Steven (if I may call you that),

Curious: You say dehumanization of the other person(s) is necessary for violence to happen, but what about the possibility of someone who has not dehumanized anyone or is not physiologically/neurologically incapable of feeling empathy towards others, but nonetheless gets pleasure out of or enjoys the suffering and/or misfortune of others?

Is the above described kind of individual impossible to exist in your opinion, or if they aren’t you think they have to be mentally or neurologically damaged or disabled in some way to feel/do such things? They can’t just be a relatively “normal” human being who just happens to harbor some dark/maladaptive desires or impulses?

Hi, thanks for writing. I anticipated sadists but didn’t want to make the piece longer than it already was. That’s why I wrote: “With rare exceptions, [violence] is a reaction to a perceived threat.” The rare exceptions I had in mind are those who directly derive pleasure from the suffering of others. Now that you mention it, this group may be larger than I initially pictured if violent psychopaths are included as well. All the same, such individuals generate a very small proportion of all the violence out there.

Psychopaths lack empathy by definition; in that sense they always dehumanize others. We don’t know the cause of psychopathy, nor whether the lack of empathy and remorse that characterizes it is organic, psychological, or some combination of the two.

So, in your opinion, someone who desires or commits violence cannot simultaneously or at least at other points in time be able to feel empathy or compassion towards others? Someone has to be a “sociopath” or “psychopath” (which, obviously, suggests something is neurologically or psychologically wrong/disabled with them) in order to feel and do such things?

Of course not. My whole post was about violence done by the great majority who are not psychopaths.

Apologies for further pressing the question, but I just am always curious to get a professional’s opinion on this. Is it not possible for a person to view another as a fellow human being (i.e. not of a lesser quality or “below” them in any way) and still harbor feelings of wanting to cause suffering and/or misfortune to them because they enjoy it?

In human psychology it’s risky to ever say something is “not possible.” It’s certainly unusual to want to cause suffering or misfortune in another while prizing his or her humanity. Guilt would generally prevent this, although in true sadism, where sexual pleasure is derived from violence and may overcome guilt, I imagine it happens. Much more common is momentarily overlooking the victim’s humanity, and then feeling guilt later when it is remembered.